Multiple Linear Regression

Example Multiple Linear Regression 1.3¶

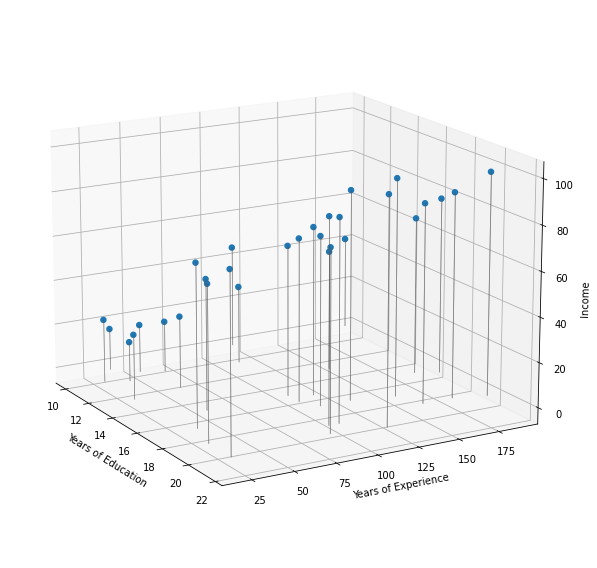

Until now, we have considered only one predictor in the Income data set: years of education. However the income depends obviously as well on the years of experience.

Thus, we have the following multiple regression model

Since we only have two predictors, the data points can be visualized in a 3D plot.

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Load data

df = pd.read_csv('Multiple Linear Regression/data/Income2.csv')

x = df['education']

y = df['experience']

z = df['income']

# Create Figure and plot

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(8, 8))

ax = plt.axes(projection="3d")

# Barplot creating vertical lines

dx, dy = 0.05, 0.05 # dx = dy, dimensions of bar

dz = z # dz = heigth of bar

ax.bar3d(x, y, [0], # Position of base

dx, dy, dz, # bar Dimensions

color='grey', alpha=0.5,

linestyle='-')

# 3D scatterplot

ax.scatter(x, y, z, alpha=1, linewidth=2)

ax.view_init(elev=16., azim=-30)

# Set titles

ax.set_xlabel('Years of Education')

ax.set_ylabel('Years of Experience')

ax.set_zlabel('Income')

# Show plot

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Contrary to the simple linear regression model, in a three-dimensional setting, with two predictors and one response, the least squares regression line becomes a plane which fits best the data points.

The plane is chosen to minimize the sum of the squared vertical distances between each observation and the plane. These vertical distances correspond to the residuals. The figure displays blue segments for points that lie above the plane, and red segments for points that lie below the plane.

The parameters are estimated using the same least squares approach that we saw in the context of simple linear regression. With the .params attribute of a fitted model we can determine the regression coefficients and for the Income data set:

import statsmodels.api as sm

# Fit Linear Model

x_sm = df[['education', 'experience']]

x_sm = sm.add_constant(x_sm)

model = sm.OLS(z, x_sm).fit()

# Print Model Parameters

print(model.params)const -50.085639

education 5.895556

experience 0.172855

dtype: float64

Example Multiple Linear Regression 2.1¶

In Python we estimate the coefficients for the linear regression model of example 1.2 for the Advertising data set, as follows

import pandas as pd

import statsmodels.api as sm

# Load data

df = pd.read_csv('Multiple Linear Regression/data/Advertising.csv')

x = df[['TV', 'radio', 'newspaper']]

y = df['sales']

# Fit Model:

x_sm = sm.add_constant(x)

model = sm.OLS(y, x_sm).fit()

# Print Model parameters

print(model.params)const 2.938889

TV 0.045765

radio 0.188530

newspaper -0.001037

dtype: float64

As we have seen, the regression coefficient estimates seem to be very different for some of the predictors with regard to the linear regression. In order to investigate this, we check how the predictors are correlated, using the DataFrame.corr() method.

# Save the Sales data in a fitting dataframe:

df = df[['TV', 'radio', 'newspaper', 'sales']]

# Print the correlation coefficients

print(df.corr()) TV radio newspaper sales

TV 1.000000 0.054809 0.056648 0.782224

radio 0.054809 1.000000 0.354104 0.576223

newspaper 0.056648 0.354104 1.000000 0.228299

sales 0.782224 0.576223 0.228299 1.000000

model.summary()Example Multiple Linear Regression 3.1¶

The -statistic for the multiple linear regression model in the Advertising example is obtained by regressing sales onto radio, TV, and newspaper and is in this example 570. In the Python-output we find the value of the -statistic under F-statistic.

import pandas as pd

import statsmodels.api as sm

# Load data

df = pd.read_csv('Multiple Linear Regression/data/Advertising.csv')

x = df[['TV', 'radio', 'newspaper']]

y = df['sales']

# Fit Model:

x_sm = sm.add_constant(x)

model = sm.OLS(y, x_sm).fit()

# Print summary including F-Statistic

print(model.summary()) OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: sales R-squared: 0.897

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 0.896

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 570.3

Date: Fri, 11 Mar 2022 Prob (F-statistic): 1.58e-96

Time: 17:24:49 Log-Likelihood: -386.18

No. Observations: 200 AIC: 780.4

Df Residuals: 196 BIC: 793.6

Df Model: 3

Covariance Type: nonrobust

==============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const 2.9389 0.312 9.422 0.000 2.324 3.554

TV 0.0458 0.001 32.809 0.000 0.043 0.049

radio 0.1885 0.009 21.893 0.000 0.172 0.206

newspaper -0.0010 0.006 -0.177 0.860 -0.013 0.011

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 60.414 Durbin-Watson: 2.084

Prob(Omnibus): 0.000 Jarque-Bera (JB): 151.241

Skew: -1.327 Prob(JB): 1.44e-33

Kurtosis: 6.332 Cond. No. 454.

==============================================================================

Notes:

[1] Standard Errors assume that the covariance matrix of the errors is correctly specified.

Since this is far larger than 1, it provides compelling evidence against the null hypothesis . In other words, the large -statistic suggests that at least one of the advertising media must be related to sales.

model.mse_resid2.8409452188887103import numpy as np

np.sqrt(model.mse_resid)1.685510373414744Example Multiple Linear Regression 3.5¶

We use a confidence interval to quantify the uncertainty surrounding the average sales over a large number of cities. We restrict ourselves to the regression of sales on TV and radio since newspaper can be neglected as followed from the previous discussion.

For example, given that CHF 100000 is spent on TV advertising and CHF 20000 is spent on radio advertising in each city, the confidence interval is

import pandas as pd

import statsmodels.api as sm

# Load data

df = pd.read_csv('Multiple Linear Regression/data/Advertising.csv')

x = df[['TV', 'radio']]

y = df['sales']

# Fit Model:

x_sm = sm.add_constant(x)

model = sm.OLS(y, x_sm).fit()

# Get prediction and confidence interval at x = [100, 20]

x0 = [[100, 20]]

x0 = sm.add_constant(x0, has_constant='add')

predictionsx0 = model.get_prediction(x0)

predictionsx0 = predictionsx0.summary_frame(alpha=0.05)

# Print the results. mean_ci_ corresponds to the confidence interval

# whereas obs_ci corresponds to the prediction interval

print(predictionsx0)

mean mean_se mean_ci_lower mean_ci_upper obs_ci_lower \

0 11.256466 0.137526 10.985254 11.527677 7.929616

obs_ci_upper

0 14.583316

We interpret this to mean that of intervals of this form will contain the true value of . In other words, if we collect a large number of data sets like the Advertising data set, and we construct a confidence interval for the average sales on the basis of each data set - given CHF 100000 in TV and CHF 20000 in radio advertising - then of these confidence intervals will contain the true value of average sales.

On the other hand, a prediction interval can be used to quantify the uncertainty surrounding sales for a particular city. Given that CHF 100000 is spent on TV and CHF 20000 is spent on radio advertising in that city the prediction interval is

We interpret this to mean that of intervals of this form will contain the true value of for this city.

Note that both intervals are centered at 11256, but that the prediction interval is substantially wider than the confidence interval, reflecting the increased uncertainty about sales for a given city in comparison to the average sales over many locations.

Example Multiple Linear Regression 4.1¶

For the Advertising data we had the following multiple linear regression model

For instance, as we discussed earlier, the p-values associated with this model indicate that TV and radio are related to sales, but that there is no evidence that newspaper is associated with sales, in the presence of these two.

We now compare the large model defined by the equation above with the small model (without newspaper)

We use the anova_lm() method function, which performs an analysis of variance (ANOVA, using an F-test) in order to test the null hypothesis that the small model is sufficient to explain the data against the alternative hypothesis that the (more complex) model is required. In order to use the anova() function, and must be nested models: the predictors in must be a subset of the predictors in . This corresponds to the null hypothesis , that is, that there is no relationship between newspaper and sales.

The Python-output provides us with the information that the residual sum of squares (RSS) in the small model is given by

whereas the residual sum of squares for the large model is

import pandas as pd

import statsmodels.api as sm

# Load data

df = pd.read_csv('Multiple Linear Regression/data/Advertising.csv')

x1 = df[['TV', 'radio']]

x2 = df[['TV', 'radio', 'newspaper']]

y = df['sales']

# Fit model

x1_sm = sm.add_constant(x1)

x2_sm = sm.add_constant(x2)

model1 = sm.OLS(y, x1_sm).fit()

model2 = sm.OLS(y, x2_sm).fit()

# Table and print results

table = sm.stats.anova_lm(model1, model2)

print(table) df_resid ssr df_diff ss_diff F Pr(>F)

0 197.0 556.913980 0.0 NaN NaN NaN

1 196.0 556.825263 1.0 0.088717 0.031228 0.859915

The difference between and can be found in the Python-output under ss_diff and is 0.088717. The value of is displayed under and is given here by 1. For the large model, we have

degrees of freedom (df_resid), contrary to the small model that has

degrees of freedom. Thus, the value of the F-statistic is (F)

The one-sided p-value in upwards direction for the -statistic assuming the null hypothesis is true, that is , is displayed in the Python-output under Pr(F) : 0.8599.

Since this p-value is significantly larger than the significance level , there is no evidence to reject the null hypothesis. We conclude that the predictor newspaper is redundant, and we therefore can omit it.

Example Multiple Linear Regression 4.3¶

If we compare the large model with the small model (TV is omitted)

then we come to a very different conclusion:

# Load data

x3 = df[['radio', 'newspaper']]

# Fit model

x3_sm = sm.add_constant(x3)

model3 = sm.OLS(y, x3_sm).fit()

# Table and print results

table = sm.stats.anova_lm(model3, model2)

print(table)

df_resid ssr df_diff ss_diff F Pr(>F)

0 197.0 3614.835279 0.0 NaN NaN NaN

1 196.0 556.825263 1.0 3058.010016 1076.405837 1.509960e-81

In this case the p-value is approximately zero, hence we have to reject the null hypothesis . There is a significant difference in how well the two models and fit the data. Omitting TV leads to a model that shows a significant deterioration with respect to the quality of the model.

In order to get an “overview” about how the quality of a model changes when one predictor variable is omitted, we can use the anova_lm() method on the one model only. However, this only works, when the model is defined using a formula instead of columns of data.

import statsmodels.formula.api as smf

# Load data

TV = df[['TV']]

radio = df[['radio']]

newspaper = df[['newspaper']]

sales = df['sales']

# Fit model using formula:

model_f = smf.ols(formula='sales ~ TV + radio + newspaper', data=df).fit()

# Table and print results

table_f = sm.stats.anova_lm(model_f, typ=2)

print(table_f) sum_sq df F PR(>F)

TV 3058.010016 1.0 1076.405837 1.509960e-81

radio 1361.736549 1.0 479.325170 1.505339e-54

newspaper 0.088717 1.0 0.031228 8.599151e-01

Residual 556.825263 196.0 NaN NaN

Example Multiple Linear Regression 4.4¶

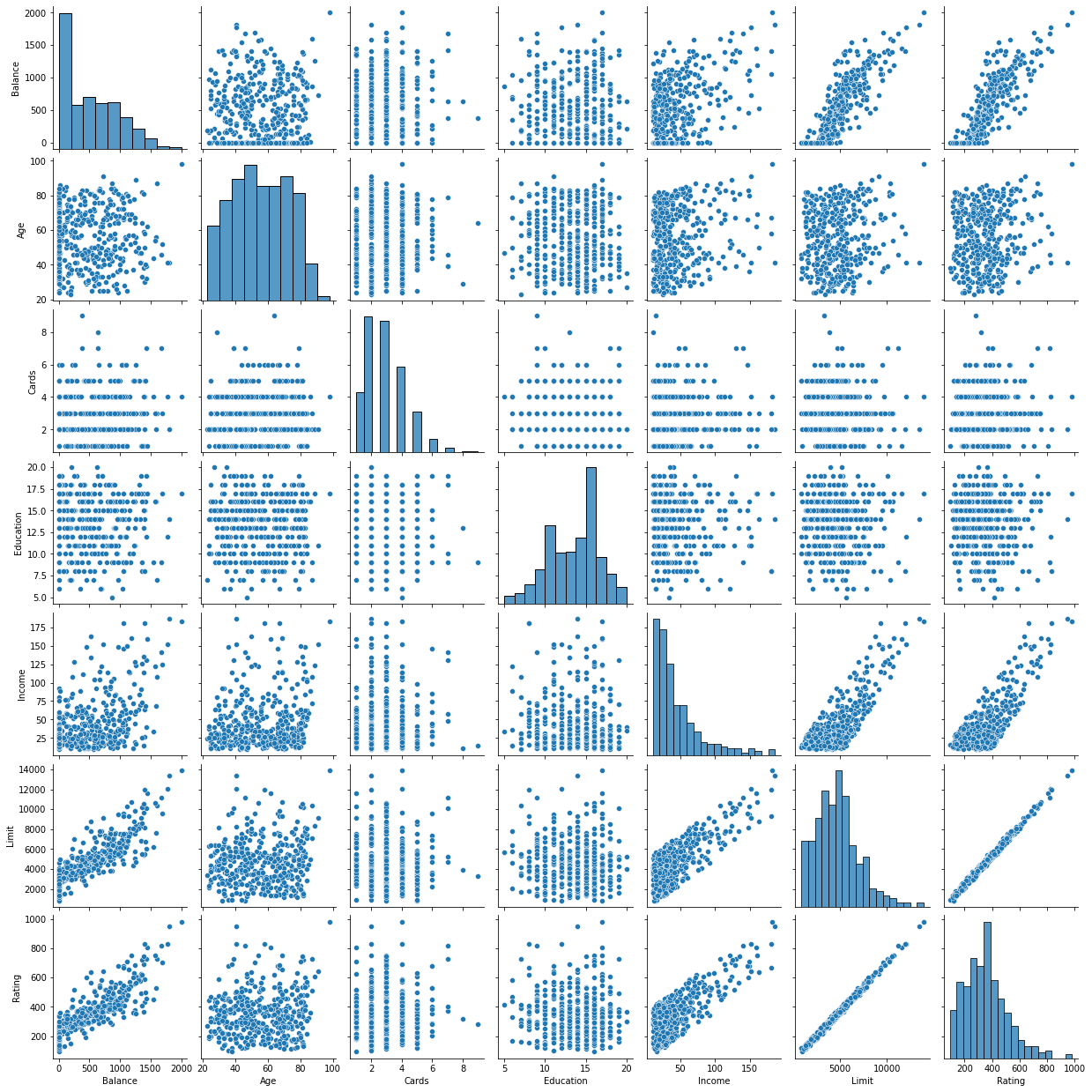

For example, the Credit data set records balance (average credit card debt for a number of individuals) as well as several quantitative predictors: age, cards (number of credit cards), education (years of education), income (in thousand of dollars), limit (credit limit), and rating (credit rating).

Each panel of the Figure is a scatterplot for a pair of variables whose identities are given by the corresponding row and column labels. For example, the scatterplot directly to the right of the word Balance depicts balance versus age, while the plot directly to the right of Age corresponds to age versus cards.

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Load data

df = pd.read_csv('Multiple Linear Regression/data/Credit.csv')

# Drop Qualitative terms / take only quantitave terms

df = df[['Balance', 'Age', 'Cards', 'Education',

'Income', 'Limit', 'Rating']]

# Plot using sns.pairplot

sns.pairplot(df)

plt.show()

In addition to these quantitative variables, we also have four qualitative variables : gender, student (student status), status (marital status) and ethnicity (Caucasian, African American or Asian).

Example Multiple Linear Regression 4.5¶

For example, based on the gender variable, we can create a new variable that takes the form

and use this variable as a predictor in the regression equation. This results in the model

Now, can be interpreted as the average credit card balance among males, as the average credit card balance among females, and as the average difference in credit card balance between females and males.

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import statsmodels.api as sm

# Load data

df = pd.read_csv('Multiple Linear Regression/data/Credit.csv')

balance = df['Balance']

# Initiate dummy variable with zeros:

gender = np.zeros(len(balance))

# Make 1 for Female:

indices_Fem = df[df['Gender']=='Female'].index.values

gender[indices_Fem] = 1

# Fit model

gender_sm = sm.add_constant(gender)

model = sm.OLS(balance, gender_sm).fit()

# Print summary:

print(model.summary()) OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: Balance R-squared: 0.000

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: -0.002

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 0.1836

Date: Fri, 11 Mar 2022 Prob (F-statistic): 0.669

Time: 18:05:36 Log-Likelihood: -3019.3

No. Observations: 400 AIC: 6043.

Df Residuals: 398 BIC: 6051.

Df Model: 1

Covariance Type: nonrobust

==============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const 509.8031 33.128 15.389 0.000 444.675 574.931

x1 19.7331 46.051 0.429 0.669 -70.801 110.267

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 28.438 Durbin-Watson: 1.940

Prob(Omnibus): 0.000 Jarque-Bera (JB): 27.346

Skew: 0.583 Prob(JB): 1.15e-06

Kurtosis: 2.471 Cond. No. 2.66

==============================================================================

Notes:

[1] Standard Errors assume that the covariance matrix of the errors is correctly specified.

The .summary() method of a fitted model shows the encoding of the dummy variable associated with gender. The average credit card debt for males is estimated to be 509.80, whereas females are estimated to carry 19.73 in additional debt for a total of .

However, we notice that the p-value for the dummy variable is , hence it is very high. This indicates that there is no statistical evidence of a difference in average credit card balance between the genders.

Example Multiple Linear Regression 4.6¶

If we had coded males as 1 and females as 0, then the estimates for and would have been 529.53 and -19.73 respectively, leading once again to a prediction of credit card debt of for males and a prediction of 529.53 for females. This is the same result we obtained with the default coding scheme.

If we wish to change the coding scheme for the dummy variable, we can change it in Python by changing the coding scheme.

# Following Example 4.5

# Initiate dummy variable with zeros:

gender = np.zeros(len(balance))

# Make 1 for Male:

indices_Mal = df[df['Gender'] == 'Male'].index.values

gender[indices_Mal] = 1

# Fit model

gender_sm = sm.add_constant(gender)

model = sm.OLS(balance, gender_sm).fit()

# Print summary:

print(model.summary()) OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: Balance R-squared: 0.000

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 0.000

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: nan

Date: Fri, 11 Mar 2022 Prob (F-statistic): nan

Time: 18:05:36 Log-Likelihood: -3019.4

No. Observations: 400 AIC: 6041.

Df Residuals: 399 BIC: 6045.

Df Model: 0

Covariance Type: nonrobust

==============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const 520.0150 22.988 22.621 0.000 474.822 565.208

x1 0 0 nan nan 0 0

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 28.709 Durbin-Watson: 1.945

Prob(Omnibus): 0.000 Jarque-Bera (JB): 27.405

Skew: 0.582 Prob(JB): 1.12e-06

Kurtosis: 2.464 Cond. No. inf

==============================================================================

Notes:

[1] Standard Errors assume that the covariance matrix of the errors is correctly specified.

[2] The smallest eigenvalue is 0. This might indicate that there are

strong multicollinearity problems or that the design matrix is singular.

Example Multiple Linear Regression 4.7¶

Alternatively, instead of a coding scheme, we could create a dummy variable

and use this variable in the regression equation. This results in the model

Now can be interpreted as the overall credit card balance (ignoring the gender effect), and is the amount that females are above the average and males are below the average.

# Following Example 4.6

# Initiate dummy variable with ones:

gender = np.ones(len(balance))

# Make -1 for Male:

indices_Mal = df[df['Gender'] == 'Male'].index.values

gender[indices_Mal] = -1

# Fit model

gender_sm = sm.add_constant(gender)

model = sm.OLS(balance, gender_sm).fit()

# Print summary:

print(model.summary()) OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: Balance R-squared: 0.000

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 0.000

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: nan

Date: Fri, 11 Mar 2022 Prob (F-statistic): nan

Time: 18:05:37 Log-Likelihood: -3019.4

No. Observations: 400 AIC: 6041.

Df Residuals: 399 BIC: 6045.

Df Model: 0

Covariance Type: nonrobust

==============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const 520.0150 22.988 22.621 0.000 474.822 565.208

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 28.709 Durbin-Watson: 1.945

Prob(Omnibus): 0.000 Jarque-Bera (JB): 27.405

Skew: 0.582 Prob(JB): 1.12e-06

Kurtosis: 2.464 Cond. No. 1.00

==============================================================================

Notes:

[1] Standard Errors assume that the covariance matrix of the errors is correctly specified.

In this example, the estimate for would be 519.67 , halfway between the male and female averages of 509.80 and 529.53. The estimate for would be 9.87, which is half of 19.73, the average difference between females and males.

Example Multiple Linear Regression 4.8¶

For example, for the ethnicity variable which has three levels we create two dummy variables. The first could be

and the second could be

Then both of these variables can be used in the regression equation, in order to obtain the model

Now can be interpreted as the average credit card balance for African Americans, can be interpreted as the difference in the average balance between the Asian and African American categories, and can be interpreted as the difference in the average balance between the Caucasian and African American categories.

There will always be one fewer dummy variable than the number of levels.

The level with no dummy variable African American in the example - is known as the baseline.

The equation

does not make sense, since this person would be Asian and Caucasian.

From the summary below, we see that the estimated balance for the baseline, African American, is 531.00.

# Following Example 4.7

# Initiate dummy variable with zeros:

ethnicity = np.zeros((len(balance),2))

# Find indices

indices_Asi = df[df['Ethnicity'] == 'Asian'].index.values

indices_Cau = df[df['Ethnicity'] == 'Caucasian'].index.values

# Set values

ethnicity[indices_Asi, 0] = 1

ethnicity[indices_Cau, 1] = 1

# Fit model

ethnicity_sm = sm.add_constant(ethnicity)

model = sm.OLS(balance, ethnicity_sm).fit()

# Print summary:

print(model.summary()) OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: Balance R-squared: 0.000

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: -0.005

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 0.04344

Date: Fri, 11 Mar 2022 Prob (F-statistic): 0.957

Time: 18:05:37 Log-Likelihood: -3019.3

No. Observations: 400 AIC: 6045.

Df Residuals: 397 BIC: 6057.

Df Model: 2

Covariance Type: nonrobust

==============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const 531.0000 46.319 11.464 0.000 439.939 622.061

x1 -18.6863 65.021 -0.287 0.774 -146.515 109.142

x2 -12.5025 56.681 -0.221 0.826 -123.935 98.930

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 28.829 Durbin-Watson: 1.946

Prob(Omnibus): 0.000 Jarque-Bera (JB): 27.395

Skew: 0.581 Prob(JB): 1.13e-06

Kurtosis: 2.460 Cond. No. 4.39

==============================================================================

Notes:

[1] Standard Errors assume that the covariance matrix of the errors is correctly specified.

It is estimated that the Asian category will have less debt than the African American category, and that the Caucasian category will have 12.50 less debt than the African American category. However, the p-values associated with the coefficient estimates for the two dummy variables are very large, suggesting no statistical evidence of a real difference in credit card balance between the ethnicities. Once again, the level selected as the baseline category is arbitrary, and the final predictions for each group will be the same regardless of this choice. However, the coefficients and their p-values do depend on the choice of dummy variable coding. Rather than rely on the individual coefficients, we can use an F-test to test

The p-value does not depend on the coding. This F-test has a p-value of 0.96, indicating that we cannot reject the null hypothesis that there is no relationship between balance and ethnicity.

Example Multiple Linear Regression 4.11¶

We now return to the Advertising example. A linear model that uses radio, TV, and an interaction between the two to predict sales takes the form

We can interpret as the increase in the effectiveness of TV advertising for a one unit increase in radio advertising (or vice-versa). The coefficients that result from fitting this model can be found in the following Python-output:

import pandas as pd

import statsmodels.api as sm

# Load data

df = pd.read_csv('Multiple Linear Regression/data/Advertising.csv')

# Define the linear model:

x = pd.DataFrame({

'TV' : df['TV'],

'radio' : df['radio'],

'TV*radio' : df['TV'] * df['radio']})

y = df['sales']

# Fit model

x_sm = sm.add_constant(x)

model =sm.OLS(y, x_sm).fit()

# Print summary:

print(model.summary()) OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: sales R-squared: 0.968

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 0.967

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 1963.

Date: Fri, 11 Mar 2022 Prob (F-statistic): 6.68e-146

Time: 18:27:43 Log-Likelihood: -270.14

No. Observations: 200 AIC: 548.3

Df Residuals: 196 BIC: 561.5

Df Model: 3

Covariance Type: nonrobust

==============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const 6.7502 0.248 27.233 0.000 6.261 7.239

TV 0.0191 0.002 12.699 0.000 0.016 0.022

radio 0.0289 0.009 3.241 0.001 0.011 0.046

TV*radio 0.0011 5.24e-05 20.727 0.000 0.001 0.001

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 128.132 Durbin-Watson: 2.224

Prob(Omnibus): 0.000 Jarque-Bera (JB): 1183.719

Skew: -2.323 Prob(JB): 9.09e-258

Kurtosis: 13.975 Cond. No. 1.80e+04

==============================================================================

Notes:

[1] Standard Errors assume that the covariance matrix of the errors is correctly specified.

[2] The condition number is large, 1.8e+04. This might indicate that there are

strong multicollinearity or other numerical problems.

The results strongly suggest that the model that includes the interaction term is superior to the model that contains only main effects. The p-value for the interaction term, , is extremely low, indicating that there is a strong evidence for . In other words it is clear, that the true relationship is not additive.

The for the model, that includes in addition to the predictors TV and radio as well the interaction term , is 0.968; compared to only 0.897 for the model that predicts sales using TV and radio without an interaction term. This means, that

of the variability in sales that remains after fitting the additive model has been explained by the interaction term. Python-output suggest that an increase in TV advertising of CHF 1000 is associated with increased sales of

units. And an increase in radio advertising of CHF 1000 will be associated with an increase in sales of

units.

Example Multiple Linear Regression 4.13¶

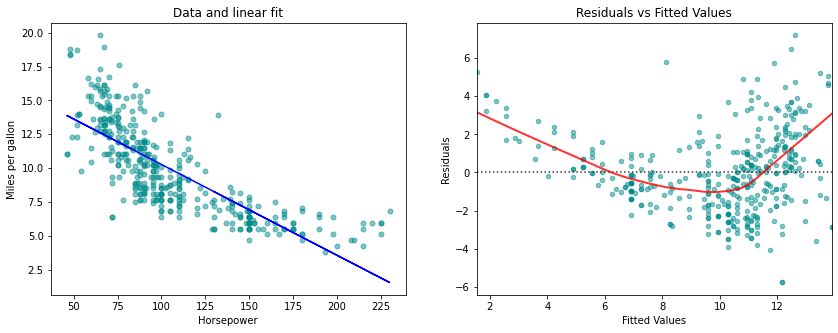

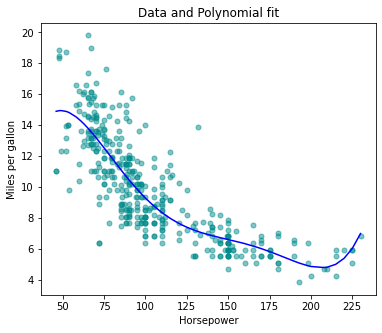

Consider the left-hand panel of the Figure, in which the mpg (gas mileage in miles per gallon) versus horsepower is shown for a number of cars in the Auto data set. The blue line represents the linear regression fit.

import pandas as pd

import statsmodels.api as sm

import seaborn as sns

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

# Load data

df = pd.read_csv(

'Multiple Linear Regression/data/Auto.csv')

# Define the linear model:

x = df['horsepower']

y = df['mpg']

# Fit model

x_sm = sm.add_constant(x)

model = sm.OLS(y, x_sm).fit()

# Create figure:

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(14, 5))

# Plot left figure: Scatter data and linear fit

ax1 = fig.add_subplot(1, 2, 1)

# Scatter data

plt.plot(x, y, marker='o', linestyle='None',

color='darkcyan', markersize='5', alpha=0.5,

label="Scatter data")

# Linear fit

plt.plot(x, model.fittedvalues, 'b-', label="Linear fit")

# Set labels

ax1.set_title('Data and linear fit')

ax1.set_xlabel('Horsepower')

ax1.set_ylabel('Miles per gallon')

# Plot right figure: Residuals vs fitted data

ax2 = fig.add_subplot(1, 2, 2)

# Residuals vs fitted value, using seaborn

ax2 = sns.residplot(

x=model.fittedvalues, y=model.resid,

data=df, lowess=True,

scatter_kws={'color': 'darkcyan', 's': 20, 'alpha': 0.5},

line_kws={'color': 'red', 'lw': 2, 'alpha': 0.8})

# Set labels

ax2.set_title('Residuals vs Fitted Values')

ax2.set_ylabel('Residuals')

ax2.set_xlabel('Fitted Values')

# Show plot

plt.show()

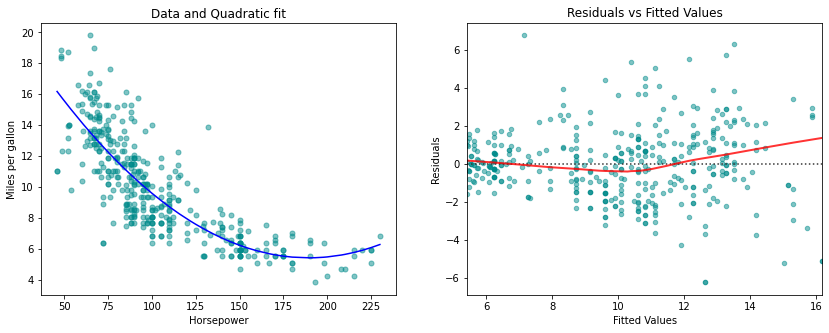

A simple approach for incorporating non-linear associations in a linear model is to include transformed versions of the predictors in the model. For example, the points in the figure seem to have a quadratic shape, suggesting that a model of the form

may provide a better fit. The equation involves predicting mpg using a non-linear function of horsepower.

But it is still a linear model!

That is, the current model is simply a multiple linear regression model with

So we can use standard linear regression software to estimate , , and in order to produce a non-linear fit.

# Define the linear model:

x = pd.DataFrame({

'horsepower' : df['horsepower'],

'horsepower^2' : (df['horsepower'] * df['horsepower'])})

y = df['mpg']

# Fit model

x_sm = sm.add_constant(x)

model = sm.OLS(y, x_sm).fit()

# Print summary:

print(model.summary()) OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: mpg R-squared: 0.688

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 0.686

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 428.0

Date: Wed, 16 Mar 2022 Prob (F-statistic): 5.40e-99

Time: 08:18:46 Log-Likelihood: -797.76

No. Observations: 392 AIC: 1602.

Df Residuals: 389 BIC: 1613.

Df Model: 2

Covariance Type: nonrobust

================================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const 24.1825 0.765 31.604 0.000 22.678 25.687

horsepower -0.1981 0.013 -14.978 0.000 -0.224 -0.172

horsepower^2 0.0005 5.19e-05 10.080 0.000 0.000 0.001

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 16.158 Durbin-Watson: 1.078

Prob(Omnibus): 0.000 Jarque-Bera (JB): 30.662

Skew: 0.218 Prob(JB): 2.20e-07

Kurtosis: 4.299 Cond. No. 1.29e+05

==============================================================================

Notes:

[1] Standard Errors assume that the covariance matrix of the errors is correctly specified.

[2] The condition number is large, 1.29e+05. This might indicate that there are

strong multicollinearity or other numerical problems.

# Create figure:

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(14, 5))

# Plot left figure: Scatter data and linear fit

ax1 = fig.add_subplot(1, 2, 1)

# Scatter data

plt.plot(x['horsepower'], y, marker='o', linestyle='None',

color='darkcyan', markersize='5', alpha=0.5,

label="Scatter data")

# Quadratic fit

x_quad_fit = x.sort_values(by='horsepower')

y_quad_fit = (model.params['const']

+ x_quad_fit['horsepower'] * model.params['horsepower']

+ x_quad_fit['horsepower^2'] * model.params['horsepower^2'])

plt.plot(x_quad_fit['horsepower'], y_quad_fit,

'b-', label="Quadratic fit")

# Set labels

ax1.set_title('Data and Quadratic fit')

ax1.set_xlabel('Horsepower')

ax1.set_ylabel('Miles per gallon')

# Plot right figure: Residuals vs fitted data

ax2 = fig.add_subplot(1, 2, 2)

# Residuals vs fitted value, using seaborn

ax2 = sns.residplot(

x=model.fittedvalues, y=model.resid,

data=df, lowess=True,

scatter_kws={'color': 'darkcyan', 's': 20, 'alpha': 0.5},

line_kws={'color': 'red', 'lw': 2, 'alpha': 0.8})

# Set labels

ax2.set_title('Residuals vs Fitted Values')

ax2.set_ylabel('Residuals')

ax2.set_xlabel('Fitted Values')

# Show plot

plt.show()

The blue curve shows the resulting quadratic fit to the data. The quadratic fit appears to be substantially better than the fit obtained before, where just the linear term is included. The of the quadratic fit is , compared to for the linear fit, and the p-value for the quadratic term is highly significant.

Let us as well perform an ANOVA-analysis

# Define the linear model:

x = pd.DataFrame({

'horsepower' : df['horsepower'],

'horsepower^2' : (df['horsepower'] * df['horsepower']),

'horsepower^3' : (df['horsepower'] ** 3),

'horsepower^4' : (df['horsepower'] ** 4),

'horsepower^5' : (df['horsepower'] ** 5),

})

y = df['mpg']

# Fit model

x_sm = sm.add_constant(x)

model =sm.OLS(y, x_sm).fit()

# Print summary:

# print(model.summary())

# Create figure:

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6, 5))

# Plot left figure: Scatter data and polynomial fit

ax1 = fig.add_subplot(1, 1, 1)

# Scatter data

plt.plot(x['horsepower'], y, marker='o', linestyle='None',

color='darkcyan', markersize='5', alpha=0.5,

label="Scatter data")

# Polynomial fit

x_quad_fit = x.sort_values(by='horsepower')

y_quad_fit = (model.params['const']

+ x_quad_fit['horsepower'] * model.params['horsepower']

+ x_quad_fit['horsepower^2'] * model.params['horsepower^2']

+ x_quad_fit['horsepower^3'] * model.params['horsepower^3']

+ x_quad_fit['horsepower^4'] * model.params['horsepower^4']

+ x_quad_fit['horsepower^5'] * model.params['horsepower^5'])

plt.plot(x_quad_fit['horsepower'], y_quad_fit,

'b-', label="Polynomial fit")

# Set labels

ax1.set_title('Data and Polynomial fit')

ax1.set_xlabel('Horsepower')

ax1.set_ylabel('Miles per gallon')

# Show plot

plt.show()

The p-value for the null hypothesis, , is approximately zero. We thus reject the null hypothesis and conclude that including the quadratic term in the regression model is essential for fitting an appropriate model to the data.

If including led to such a big improvement in the model, why not include , or even ? The Figure displays the fit that results from including all polynomials up to fifth degree in the model. The resulting fit seems unnecessarily wiggly - that is, it is unclear that including the additional terms really has led to a better fit to the data.

The approach that we have just described for extending the linear model to accomodate non-linear relationships is known as polynomial regression, since we have included polynomial functions of the predictors in the regression model.

Example Multiple Linear Regression 4.14¶

Let us consider the following model

and the model that includes as well the interaction term

We have omitted the predictor newspaper, since we came to the conclusion that newspaper is not relevant to predict sales.

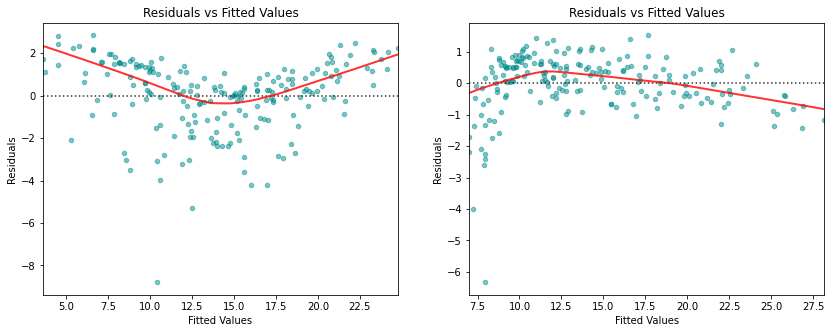

The figure displays the Tukey-Anscombe plots for these two models. The right-hand panel displays the Tukey-Anscombe plot for the model where the interaction term is included, in the left-hand panel the Tukey-Anscombe plot for the model without interaction term is shown. We observe that there is a clear improvement of the smoothing curve, when the interaction term is included in the model.

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

import statsmodels.api as sm

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

# Load data

df = pd.read_csv('Multiple Linear Regression/data/Advertising.csv')

# Define the linear models:

x_plain = pd.DataFrame({

'TV' : df['TV'],

'radio' : df['radio']})

x_inter = pd.DataFrame({

'TV' : df['TV'],

'radio' : df['radio'],

'TV*radio' : df['TV'] * df['radio']})

y = df['sales']

# Fit models

# Plain model

x_plain_sm = sm.add_constant(x_plain)

model_plain = sm.OLS(y, x_plain_sm).fit()

# Model including interaction term

x_inter_sm = sm.add_constant(x_inter)

model_inter = sm.OLS(y, x_inter_sm).fit()# Create figure:

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(14, 5))

# Plot left figure: Residuals vs fitted data

ax1 = fig.add_subplot(1, 2, 1)

# Scatter data

ax1 = sns.residplot(

x=model_plain.fittedvalues, y=model_plain.resid,

data=df, lowess=True,

scatter_kws={'color': 'darkcyan', 's': 20, 'alpha': 0.5},

line_kws={'color': 'red', 'lw': 2, 'alpha': 0.8})

# Set labels

ax1.set_title('Residuals vs Fitted Values')

ax1.set_ylabel('Residuals')

ax1.set_xlabel('Fitted Values')

# Plot left figure: Residuals vs fitted data

ax1 = fig.add_subplot(1, 2, 2)

# Scatter data

ax2 = sns.residplot(

x=model_inter.fittedvalues, y=model_inter.resid,

data=df, lowess=True,

scatter_kws={'color': 'darkcyan', 's': 20, 'alpha': 0.5},

line_kws={'color': 'red', 'lw': 2, 'alpha': 0.8})

# Set labels

ax2.set_title('Residuals vs Fitted Values')

ax2.set_ylabel('Residuals')

ax2.set_xlabel('Fitted Values')

# Show plot

plt.show()

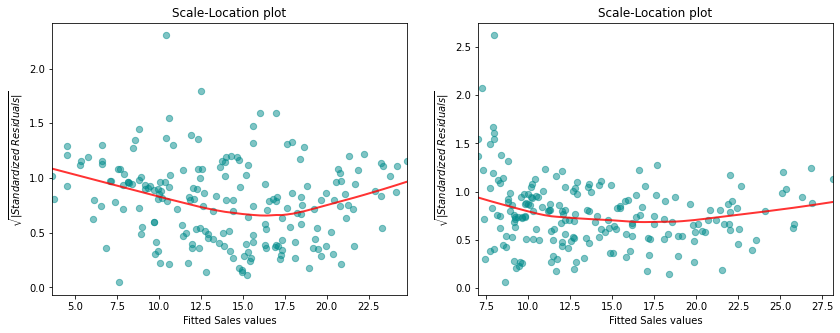

In the right-hand panel the scale-location plot for the model considering the interaction term is displayed, the left-hand panel displays the scale-location plot for the model without interaction term. We observe again an improvement of the smoothing curve in the sense that including the interaction term leads to a rather constant smoother.

import numpy as np

# Residuals of the model

res_plain = model_plain.resid

res_inter = model_inter.resid

# Influence of the Residuals

res_inf_plain = model_plain.get_influence()

res_inf_inter = model_inter.get_influence()

# Studentized residuals using variance from OLS

res_standard_plain = res_inf_plain.resid_studentized_internal

res_standard_inter = res_inf_inter.resid_studentized_internal

# Absolute square root Residuals:

res_stand_sqrt_plain = np.sqrt(np.abs(res_standard_plain))

res_stand_sqrt_inter = np.sqrt(np.abs(res_standard_inter))

# Create figure:

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(14, 5))

# Plot left figure: Residuals vs fitted data

ax1 = fig.add_subplot(1, 2, 1)

# plot Regression usung Seaborn

sns.regplot(x=model_plain.fittedvalues, y=res_stand_sqrt_plain,

scatter=True, ci=False, lowess=True,

scatter_kws={'color': 'darkcyan', 's': 40, 'alpha': 0.5},

line_kws={'color': 'red', 'lw': 2, 'alpha': 0.8})

ax1.set_title('Scale-Location plot')

ax1.set_xlabel('Fitted Sales values')

ax1.set_ylabel('$\sqrt{\|Standardized\ Residuals\|}$')

# Plot left figure: Residuals vs fitted data

ax2 = fig.add_subplot(1, 2, 2)

# plot Regression usung Seaborn

sns.regplot(x=model_inter.fittedvalues, y=res_stand_sqrt_inter,

scatter=True, ci=False, lowess=True,

scatter_kws={'color': 'darkcyan', 's': 40, 'alpha': 0.5},

line_kws={'color': 'red', 'lw': 2, 'alpha': 0.8})

ax2.set_title('Scale-Location plot')

ax2.set_xlabel('Fitted Sales values')

ax2.set_ylabel('$\sqrt{\|Standardized\ Residuals\|}$')

# Show plot

plt.show()

On the basis of the residual plots, we therefore conclude that the model including the interaction term fits the data better. There is however an aspect of the residual analysis for the model including the interaction term that seems problematic: the outlying observations 131 und 156.

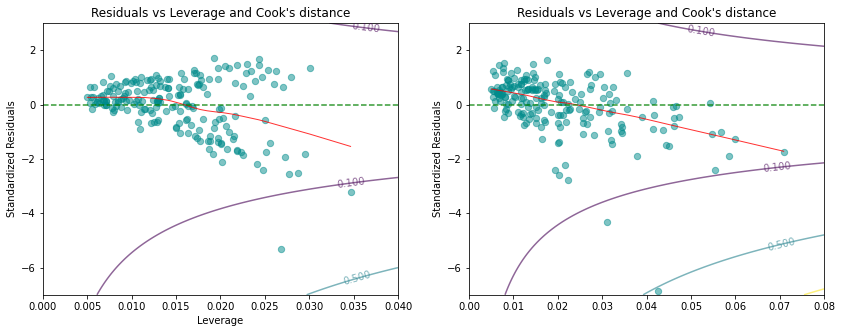

The next figure plots for every observation the leverage statistic versus the standardized residual . In multiple regression, the values of the levarage statistic are defined as diagonal elements of the hat matrix . The hat matrix is defined as

where denotes the data matrix composed of measurements, of features, and of ones in the first column. The expected value of the leverage statistic is given by

where denotes the number of predictor variables and is the number of data points. So if a given observation has a leverage statistic that greatly exceeds the expected value, that is

then we may suspect that the corresponding point has high leverage. In the previous example of the Advertising data for the model including the interaction term, we have and . Thus, a value of the leverage statistic exceeding should attract our attention.

In order to have a dangerous influence on the regression model, an observation needs to have as well a large absolute value of the residual. In simple linear regression analysis, Cook’s distance is a function of the leverage statistic and of the standardized residual . In multiple regression, Cook’s distance is defined as

where denotes the diagonal elements of the hat matrix .

The next figure displays the contour lines for the function values , , and 0.1 of Cook’s distance. Observations with a Cook’s distance larger than must be considered as dangerous.

# Cook's Distance and leverage:

res_inf_cooks_plain = res_inf_plain.cooks_distance

res_inf_cooks_inter = res_inf_inter.cooks_distance

res_inf_leverage_plain = res_inf_plain.hat_matrix_diag

res_inf_leverage_inter = res_inf_inter.hat_matrix_diag

# Contour levels for Cook's distance

n = 100 # Grid dimensions

n_pred_plain = x_plain.shape[1]

n_pred_inter = x_inter.shape[1]

xmin, ymin, ymax = 0, -7, 3 # Grid boundaries

xmax_plain, xmax_inter = 0.04, 0.08

cooks_distance_plain = np.zeros((n, n))

cooks_distance_inter = np.zeros((n, n))

# Create grid

y_cooks = np.linspace(ymin, ymax, n)

x_cooks_plain = np.linspace(xmin, xmax_plain, n)

x_cooks_inter = np.linspace(xmin, xmax_inter, n)

for xi in range(n):

for yi in range(n):

cooks_distance_plain[yi][xi] = (

y_cooks[yi]**2 * x_cooks_plain[xi] /

(1 - x_cooks_plain[xi]) / (n_pred_plain + 1))

cooks_distance_inter[yi][xi] = (

y_cooks[yi]**2 * x_cooks_inter[xi] /

(1 - x_cooks_inter[xi]) / (n_pred_inter + 1))

# Create figure:

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(14, 5))

# Plot left figure: Cook's distance

ax1 = fig.add_subplot(1, 2, 1)

# ax1.set_xlim(0, 0.04)

# Plot standardized Residuals

sns.regplot(x=res_inf_leverage_plain, y=res_standard_plain,

scatter=True, ci=False, lowess=True,

scatter_kws={'color': 'darkcyan', 's': 40, 'alpha': 0.5},

line_kws={'color': 'red', 'lw': 1, 'alpha': 0.8})

# Plot centre line

plt.plot((xmin, xmax_plain), (0, 0), 'g--', alpha=0.8)

# Plot Cook's Distance

CS = ax1.contour(x_cooks_plain, y_cooks, cooks_distance_plain,

levels=[0.1, 0.5, 1], alpha=0.6)

# labels and title

ax1.clabel(CS, inline=0, fontsize=10)

ax1.set_title('Residuals vs Leverage and Cook\'s distance')

ax1.set_xlabel('Leverage')

ax1.set_ylabel('Standardized Residuals')

# Plot left figure: Cook's distance

ax2 = fig.add_subplot(1, 2, 2)

# Plot Regression using Seaborn

sns.regplot(x=res_inf_leverage_inter, y=res_standard_inter,

scatter=True, ci=False, lowess=True,

scatter_kws={'color': 'darkcyan', 's': 40, 'alpha': 0.5},

line_kws={'color': 'red', 'lw': 1, 'alpha': 0.8})

# Plot centre line

plt.plot((xmin, xmax_inter), (0, 0), 'g--', alpha=0.8)

# Plot Cook's Distance

CS = ax2.contour(x_cooks_inter, y_cooks, cooks_distance_inter,

levels=[0.1, 0.5, 1], alpha=0.6)

# labels and title

ax2.clabel(CS, inline=0, fontsize=10)

ax2.set_title('Residuals vs Leverage and Cook\'s distance')

# ax2.set_xlabel('Leverage')

ax2.set_ylabel('Standardized Residuals')

# Show plot

plt.show()

Based on the plots we conclude that observations 156 and 131 are not dangerous.

Example Multiple Linear Regression 4.17¶

The following Python-output displays the correlation matrix for the Credit data set.

import pandas as pd

# Load data

df = pd.read_csv('Multiple Linear Regression/data/Credit.csv')

# Drop all quantitative columns

df = df.drop(['Unnamed: 0','Gender','Student','Married','Ethnicity'],

axis=1)

# Find the correlation Matrix using DataFrame.corr()

print(round(df.corr(), 4)) Income Limit Rating Cards Age Education Balance

Income 1.0000 0.7921 0.7914 -0.0183 0.1753 -0.0277 0.4637

Limit 0.7921 1.0000 0.9969 0.0102 0.1009 -0.0235 0.8617

Rating 0.7914 0.9969 1.0000 0.0532 0.1032 -0.0301 0.8636

Cards -0.0183 0.0102 0.0532 1.0000 0.0429 -0.0511 0.0865

Age 0.1753 0.1009 0.1032 0.0429 1.0000 0.0036 0.0018

Education -0.0277 -0.0235 -0.0301 -0.0511 0.0036 1.0000 -0.0081

Balance 0.4637 0.8617 0.8636 0.0865 0.0018 -0.0081 1.0000

From the Python-output we read off that the correlation coefficient between limit and age is which corresponds to a rather weak correlation. On the other hand, we find for the correlation between limit and rating a value of which is very large.

Example Multiple Linear Regression 4.18¶

In the Credit data, a regression of balance on age, rating, and limit indicates that the predictors have VIF values of 1.01, 160.67, and 160.59. As we suspected, there is considerable collinearity in the data.

import numpy as np

import statsmodels.api as sm

from statsmodels.stats.outliers_influence import variance_inflation_factor

# Define the linear model:

x = pd.DataFrame({

'Age' : df['Age'],

'Rating' : df['Rating'],

'Limit' : df['Limit']})

y = df['Balance']

# VIF Analysis

x_c = sm.add_constant(x)

VIF = []

for i in range(1,4):

VIF.append(variance_inflation_factor(x_c.to_numpy(), i))

print(list(x.columns), '\n', np.round(VIF, 3))

# R Squared for 'complete' system

# Fit models

x_sm = sm.add_constant(x)

model = sm.OLS(y, x_sm).fit()

print('\nRsquared for the complete model is given by:\n',

np.round(model.rsquared, 4))['Age', 'Rating', 'Limit']

[ 1.011 160.668 160.593]

Rsquared for the complete model is given by:

0.7536

Example Multiple Linear Regression 4.19¶

When faced with the problem of collinearity, there are two simple solutions. The first is to drop one of the problematic variables from the regression. This can usually be done without much compromise to the regression fit, since the presence of collinearity implies that the information that this variable provides about the response is redundant in the presence of the other variables.

For instance, if we regress balance onto age and limit, without the rating predictor, then the resulting VIF values are close to the minimum possible value of 1, and the drops from 0.754 to 0.75.

# Define the linear model:

x = x.drop('Rating', axis=1, errors='ignore')

# Fit models

model = sm.OLS(y, x_sm).fit()

# Print result

print('\n Rsquared without \'Rating\' is given by:\n',

np.round(model.rsquared, 4))

Rsquared without 'Rating' is given by:

0.7536

So dropping rating from the set of predictors has effectively solved the collinearity problem without compromosing the fit.

Example Multiple Linear Regression 5.1¶

We now return to the seven questions about the Advertising data that we set out to answer. To this goal, we have again a look at the Python-output of example 3.1.

import pandas as pd

import statsmodels.api as sm

# Load data

df = pd.read_csv('Multiple Linear Regression/data/Advertising.csv')

x = df[['TV', 'radio', 'newspaper']]

y = df['sales']

# Fit Model:

x_sm = sm.add_constant(x)

model = sm.OLS(y, x_sm).fit()

# Print summary including F-Statistic

print(model.summary()) OLS Regression Results

==============================================================================

Dep. Variable: sales R-squared: 0.897

Model: OLS Adj. R-squared: 0.896

Method: Least Squares F-statistic: 570.3

Date: Fri, 23 Jul 2021 Prob (F-statistic): 1.58e-96

Time: 13:56:31 Log-Likelihood: -386.18

No. Observations: 200 AIC: 780.4

Df Residuals: 196 BIC: 793.6

Df Model: 3

Covariance Type: nonrobust

==============================================================================

coef std err t P>|t| [0.025 0.975]

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

const 2.9389 0.312 9.422 0.000 2.324 3.554

TV 0.0458 0.001 32.809 0.000 0.043 0.049

radio 0.1885 0.009 21.893 0.000 0.172 0.206

newspaper -0.0010 0.006 -0.177 0.860 -0.013 0.011

==============================================================================

Omnibus: 60.414 Durbin-Watson: 2.084

Prob(Omnibus): 0.000 Jarque-Bera (JB): 151.241

Skew: -1.327 Prob(JB): 1.44e-33

Kurtosis: 6.332 Cond. No. 454.

==============================================================================

Notes:

[1] Standard Errors assume that the covariance matrix of the errors is correctly specified.

The Fitted Parameters and their confidence interval is given by:

# Print Model parameters

print(model.conf_int(alpha=0.05, cols=None)) 0 1

const 2.323762 3.554016

TV 0.043014 0.048516

radio 0.171547 0.205513

newspaper -0.012616 0.010541

import numpy as np

import statsmodels.api as sm

from statsmodels.stats.outliers_influence import variance_inflation_factor

# VIF Analysis

x_c = sm.add_constant(x)

VIF = []

for i in range(1,4):

VIF.append(variance_inflation_factor(x_c.to_numpy(), i))

print(list(x.columns), '\n', np.round(VIF, 3))['TV', 'radio', 'newspaper']

[1.005 1.145 1.145]