Summary - Advanced Deep Learning

Notebook Cell

import torch

import torch.nn as nn

import torchvision

from torchinfo import summary

from torcheval.metrics import MulticlassAccuracy

import numpy as np

import wandbNetwork Architecture Design Patterns¶

Output Size Decrease¶

Problem: The input image (e.g., 1000x1000) is too large to feed directly into a classifier (MLP), which would result in millions of parameters,.

Why: High resolution contains redundant information; we need to condense features.

Solution: Use Pooling (Max/Average) or Strided Convolutions,. Strided convolutions are preferred in modern networks as they allow the network to learn how to downsample adaptively.

# Option A: Max Pooling

torch.nn.MaxPool2d(kernel_size=2, stride=2)

# Option B: Strided Convolution (Preferred)

torch.nn.Conv2d(in_channels=64, out_channels=128,

kernel_size=3, stride=2, padding=1)Output

Conv2d(64, 128, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(2, 2), padding=(1, 1))Normalization¶

Problem: Deep networks are difficult to train and may not converge.

Why: Data distribution shifts as it travels through layers (internal covariate shift), and inputs to later layers are not normalized.

Solution: Batch Normalization. It learns to normalize data (mean 0, std 1) inside the network, enabling higher learning rates and faster training.

torch.nn.Sequential(

torch.nn.Conv2d(64, 64, kernel_size=3, padding=1),

torch.nn.BatchNorm2d(64), # Batch Normalization

torch.nn.ReLU())Output

Sequential(

(0): Conv2d(64, 64, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(1, 1), padding=(1, 1))

(1): BatchNorm2d(64, eps=1e-05, momentum=0.1, affine=True, track_running_stats=True)

(2): ReLU()

)Residual Connections¶

Problem: Adding more layers to a deep network (e.g., >30) can degrade performance and stop convergence,.

Why: Gradients vanish during backpropagation, and it is difficult for layers to learn the identity function (doing nothing) if needed

Solution: Add the input to the output of the layer , creating a Skip Connection (). This allows gradients to flow through the network easily.

class ResidualBlock(torch.nn.Module):

def forward(self, x):

identity = x

out = self.conv_layers(x) # F(x)

return out + identity # F(x) + xOutput Size Increase¶

Problem: Generative models (like autoencoders) need to reconstruct an image from a small latent vector.

Solution: Upsampling (repetition) or Transposed Convolutions. Transposed convolutions learn weights to optimally upsample the data.

# Option A: Upsampling

torch.nn.Upsample(scale_factor=2, mode='nearest')

# Option B: Transposed Convolution (Learnable)

torch.nn.ConvTranspose2d(in_channels=64,

out_channels=32, kernel_size=3, stride=2)Output

ConvTranspose2d(64, 32, kernel_size=(3, 3), stride=(2, 2))Channel Number Decrease (Bottleneck)¶

Problem: Computational cost is too high when convolutional filters operate on tensors with large depth (e.g., 256 channels).

Solution: Bottleneck Layers. Use a convolution to reduce the number of channels (e.g., to 64), perform the expensive convolution, and then scale back up.

bottleneck = torch.nn.Sequential(

# Compress:

torch.nn.Conv2d(256, 64, kernel_size=1),

# Process:

torch.nn.Conv2d(64, 64, kernel_size=3, padding=1),

# Expand:

torch.nn.Conv2d(64, 256, kernel_size=1))Deep Networks with Fewer Parameters¶

Problem: Large filters (e.g., ) have a massive number of parameters ( weights per channel).

Solution: Stack multiple small filters (e.g., ). Two stacked layers have a receptive field of but fewer parameters and more non-linearities (activation functions), making training easier.

# Replaces one large 5x5 convolution

stack = torch.nn.Sequential(

torch.nn.Conv2d(64, 64, kernel_size=3, padding=1),

torch.nn.ReLU(),

torch.nn.Conv2d(64, 64, kernel_size=3, padding=1),

torch.nn.ReLU())Multiple Resolution (Inception)¶

Problem: It is unclear which kernel size (, , or ) is best for a specific feature.

Solution: Inception Modules. Compute convolutions with different kernel sizes in parallel and concatenate the results.

class InceptionModule(torch.nn.Module):

def forward(self, x):

p1 = self.conv1x1(x)

p2 = self.conv3x3(x)

p3 = self.conv5x5(x)

# Concatenate along channel dimension:

return torch.cat([p1, p2, p3], dim=1)Faster Large Convolutions¶

Problem: Standard 2D convolutions are computationally expensive.

Solution: Separable Convolutions. Spatial Separation: Replace an filter with a and filter. Depth-wise Separation: Use a single filter per channel (Depth-wise) followed by a filter to mix channels (Point-wise),.

separable = torch.nn.Sequential(

# Depthwise: groups=in_channels => 1 filter per channel

torch.nn.Conv2d(32, 32, kernel_size=3, groups=32),

# Pointwise: 1x1 conv to mix channels

torch.nn.Conv2d(32, 64, kernel_size=1))Share Features (Multi-Head)¶

Problem: You need multiple outputs (e.g., move selection AND win probability in chess) from the same input.

Solution: Multi-headed Networks. Use a shared “backbone” to extract features, then split into separate “heads” (MLPs) for different tasks. Gradients from both heads help train the backbone.

class MultiHeadNet(torch.nn.Module):

def forward(self, x):

features = self.shared_backbone(x)

class_out = self.classification_head(features)

reg_out = self.regression_head(features)

return class_out, reg_outGenerate Sparse Layers (Dropout)¶

Problem: Overfitting; the network relies too heavily on specific neurons.

Solution: Dropout. Randomly set the output of some neurons to zero during training. This forces the network to generalize and become robust to missing data.

torch.nn.Dropout(p=0.5)Output

Dropout(p=0.5, inplace=False)Constrain Model Parameters¶

Problem: Overfitting due to large weights.

Solution: L2 Regularization (Weight Decay). Add a penalty term to the loss function proportional to the size of the weights, forcing them towards zero.

Notebook Cell

model = torch.nn.TransformerEncoder(torch.nn.TransformerEncoderLayer(d_model=512, nhead=8), num_layers=6)optimizer = torch.optim.SGD(

model.parameters(), lr=0.01, weight_decay=1e-5)PyTorch Training Pipeline¶

# Make training reproducible:

seed = 1234

np.random.seed(seed)

torch.manual_seed(seed)

torch.cuda.manual_seed(seed)

torch.backends.cudnn.deterministic = True

# Preprocess data:

transform = torchvision.transforms.Compose([

torchvision.transforms.ToTensor()])

data_train = torchvision.datasets.MNIST(

root='data/mnist', download=True,

transform=transform)

# data_test = ...MNIST(...train=False)Notebook Cell

data_test = torchvision.datasets.MNIST(root='data/mnist', train=False, download=True, transform=transform)

class SimpleCNN(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

self.layers = nn.Sequential(

nn.Conv2d(1, out_channels=4, kernel_size=3),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.MaxPool2d(2, 2),

nn.Conv2d(4, 8, 3),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.MaxPool2d(2, 2),

nn.Conv2d(8, 8, 3),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Flatten(),

nn.Linear(72, 120),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(120, 10)

)

def forward(self, x):

return self.layers.forward(x)

model = SimpleCNN()# Split data into train and validation sets:

len_train = (int)(0.8 * len(data_train))

len_val = len(data_train) - len_train

data_train_subset, data_val_subset =(

torch.utils.data.random_split(

data_train, [len_train, len_val]))

# Construct data loaders for data sets:

BATCH_SIZE = 64

data_train_loader = torch.utils.data.DataLoader(

dataset=data_train_subset, shuffle=True,

batch_size=BATCH_SIZE)

data_val_loader = torch.utils.data.DataLoader(

dataset=data_val_subset, shuffle=False,

batch_size=BATCH_SIZE)

data_test_loader = torch.utils.data.DataLoader(

data_test, batch_size=64)

wandb.login()

def train(epochs: int, model, loss_fn, optim,

metrics, device):

wandb.init(project="mnist-example",

config={'epochs': epochs,

'batch_size':

data_train_loader.batch_size})

step_count = 0

model = model.to(device)

# Training:

for epoch in range(epochs):

model.train()

metrics.reset()

for step, (inputs, labels) in\

enumerate(data_train_loader):

inputs = inputs.to(device)

labels = labels.to(device)

# Zero your gradients for every batch!

optim.zero_grad()

outputs = model(inputs)

_, predicted = torch.max(outputs, 1)

train_loss = loss_fn(outputs, labels)

train_loss.backward()

optim.step()

metrics.update(predicted, labels)

train_acc = metrics.compute()

train_metrics = {

'train/train_loss:': train_loss,

'train/train_acc': train_acc,

'train/epoch': epoch}

step_count += 1

wandb.log(train_metrics, step=step_count)

# Validation:

model.eval()

metrics.reset()

val_loss = []

val_steps = 0

for step, (inputs, labels) in\

enumerate(data_val_loader):

inputs = inputs.to(device)

labels = labels.to(device)

with torch.no_grad():

outputs = model(inputs)

_, predicted = torch.max(outputs, 1)

val_loss.append(

loss_fn(outputs, labels).item())

metrics.update(predicted, labels)

val_steps += 1

val_acc = metrics.compute()

val_loss_mean = np.mean(val_loss)

val_metrics = {'val/val_loss': val_loss_mean,

'val/val_acc' : val_acc}

wandb.log(val_metrics, step=val_steps)

print(f"Epoch {epoch:02} ...")

wandb.finish()Output

model = SimpleCNN()

metrics = MulticlassAccuracy(num_classes=10)

optim = torch.optim.Adam(model.parameters(), lr=0.001)

loss_fn = nn.CrossEntropyLoss()

device = 'cuda' if torch.cuda.is_available() else\

'mps' if torch.mps.is_available() else 'cpu'

epochs = 10

train(epochs, model, loss_fn, optim, metrics, device)Output

Epoch 00 ...

Epoch 01 ...

Epoch 02 ...

Epoch 03 ...

Epoch 04 ...

Epoch 05 ...

Epoch 06 ...

Epoch 07 ...

Epoch 08 ...

Epoch 09 ...

MLP: Multi Layer Perceptron¶

‘Simple’ Problems where the input is features

Output layers in a CNN after feature extractions

Feature transformation (for example after attention layers)

Dimensionality reduction

Each node calculates its output based in the inputs , the weights (on the edges), a bias value and the activation function :

CNN: Convolutional Neural Network¶

class SimpleCNN(nn.Module):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

self.layers = nn.Sequential(

nn.Conv2d(1,out_channels=4,kernel_size=3),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.MaxPool2d(2, 2), nn.Conv2d(4, 8, 3),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.MaxPool2d(2, 2), nn.Conv2d(8, 8, 3),

nn.ReLU(), nn.Flatten(),

nn.Linear(72, 120),nn.ReLU(),nn.Linear(120, 10))

def forward(self, x): return self.layers.forward(x)

summary(SimpleCNN(), input_size=(64, 1, 28, 28))Output

==========================================================================================

Layer (type:depth-idx) Output Shape Param #

==========================================================================================

SimpleCNN [64, 10] --

├─Sequential: 1-1 -- --

│ └─Conv2d: 2-1 [64, 4, 26, 26] 40

│ └─ReLU: 2-2 [64, 4, 26, 26] --

│ └─MaxPool2d: 2-3 [64, 4, 13, 13] --

│ └─Conv2d: 2-4 [64, 8, 11, 11] 296

│ └─ReLU: 2-5 [64, 8, 11, 11] --

│ └─MaxPool2d: 2-6 [64, 8, 5, 5] --

│ └─Conv2d: 2-7 [64, 8, 3, 3] 584

│ └─ReLU: 2-8 [64, 8, 3, 3] --

│ └─Flatten: 2-9 [64, 72] --

│ └─Linear: 2-10 [64, 120] 8,760

│ └─ReLU: 2-11 [64, 120] --

│ └─Linear: 2-12 [64, 10] 1,210

==========================================================================================

Total params: 10,890

Trainable params: 10,890

Non-trainable params: 0

Total mult-adds (Units.MEGABYTES): 5.00

==========================================================================================

Input size (MB): 0.20

Forward/backward pass size (MB): 1.98

Params size (MB): 0.04

Estimated Total Size (MB): 2.23

==========================================================================================Why CNNs?¶

In Deep Learning you usually start with raw data and you aim to learn features first - then based on these learned features, you would then try to solve the actual problem for which we can again use MLPs for example (i.e. in classification).

Fundamental Design Principles¶

Data Transformation: Standard CNNs typically decrease spatial resolution (width/height) while increasing the number of channels (depth) to extract higher-level features.

Downsampling: Accomplished via Pooling (Max/Average) or Strided Convolutions. Strided convolutions (e.g., ) are preferred in modern networks as the weights are learnable, allowing the network to adaptively reduce resolution.

Max Pooling (Downsampling)

Max Unpooling (Upsampling)

Max pooling remembers max position. Max unpooling places value at correct position. Zeros fill non-max positions.

Average Pooling (Downsampling)

Nearest Neighbor (Upsampling)

Replicates each value into 2x2 block ( scale).

Bed of Nails (Upsampling)

Zeroes fill unknown positions.

Transposed Convolution (Upsampling)

A transposed convolution performs the reverse operation of a standard convolution: it maps each input element to multiple output positions. For each input value, the kernel is multiplied and placed at different output locations.

Transposed convolutions can be understood as matrix multiplication. A standard convolution can be represented as: where is the convolution matrix (Toeplitz matrix). The transposed convolution is: . The transpose relationship gives these operations their name, though they are not true inverses - they only approximate inversion through backpropagation.

Example: 2x2 Input, 3x3 Kernel, Stride 1

Process: Each input value is multiplied by the entire kernel and placed at its output position: is multiplied by the full kernel and placed starting at output position , is multiplied and placed at (shifted by stride), is multiplied and placed at , is multiplied and placed at

Overlapping regions are summed, producing a output:

Training Stability: Residual Connections¶

Problem: Vanishing/exploding gradients make training very deep networks (e.g., >30 layers) difficult; adding layers can actually degrade performance.

Solution: Residual (Skip) Connections add the original input to the output of a layer block , resulting in . This allows gradients to flow more easily through “shortcuts”.

CNN Formulae¶

class depthwise_separable_conv(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, in_ch: int, out_ch: int,

kernel_size = 3,

padding = 1, bias=False):

super(depthwise_separable_conv, self).__init__()

self.depthwise = nn.Conv2d(in_ch, in_ch,

kernel_size, padding=padding, groups=in_ch,

bias=bias)

self.pointwise = nn.Conv2d(in_ch, out_ch,

kernel_size=1, bias=bias)

def forward(self, x):

return self.pointwise(self.depthwise(x))def bottleneck(self, in_ch: int, out_ch: int,

stride, padding):

btl_ch = out_ch // 4 # bottleneck channels

return nn.Sequential(

nn.BatchNorm2d(in_ch),

nn.ReLU(True),

# conv 1x1:

nn.Conv2d(in_ch, btl_ch, kernel_size=1,

stride=stride, padding=0),

# conv 3x3:

nn.BatchNorm2d(btl_ch),

nn.ReLU(True),

nn.Conv2d(btl_ch, btl_ch, kernel_size=3,

stride=1, padding=padding),

# conv 1x1:

nn.BatchNorm2d(btl_ch),

nn.ReLU(True),

nn.Conv2d(btl_ch, out_ch, kernel_size=1,

stride=1, padding=0))Auto-Encoder (AE)¶

The Auto-Encoder is a neural network designed to learn efficient data codings in an unsupervised manner. It forces the network to learn the most significant features of the data by compressing it into a lower-dimensional space.

Encoder: Compresses the input into a small latent vector using convolutional layers and downsampling (e.g., strided convolutions or pooling).

Decoder: Reconstructs the image from the latent vector using upsampling techniques like Transposed Convolutions or Upsampling layers.

Objective: Minimize the Reconstruction Loss (typically Mean Squared Error) between the input image and the reconstructed output.

Use Case: Dimensionality reduction, feature extraction, and denoising.

class Encoder(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, latent_dims):

super(Encoder, self).__init__()

self.linear1 = nn.Linear(784, 512)

self.linear2 = nn.Linear(512, latent_dims)

def forward(self, x):

x = torch.flatten(x, start_dim=1) # (batch_size, 784)

x = nn.functional.relu(self.linear1(x))

return self.linear2(x) # Output latent representation

class Decoder(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, latent_dims):

super(Decoder, self).__init__()

self.linear1 = nn.Linear(latent_dims, 512)

self.linear2 = nn.Linear(512, 784)

def forward(self, z):

z = nn.functional.relu(self.linear1(z))

z = torch.sigmoid(self.linear2(z)) # Map to [0, 1]

return z.reshape((-1, 1, 28, 28)) # (batch_size, 1, 28, 28)

class Autoencoder(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, latent_dims):

super(Autoencoder, self).__init__()

self.encoder = Encoder(latent_dims)

self.decoder = Decoder(latent_dims)

def forward(self, x):

z = self.encoder(x)

return self.decoder(z) # Reconstructed imageRecurrent Architectures¶

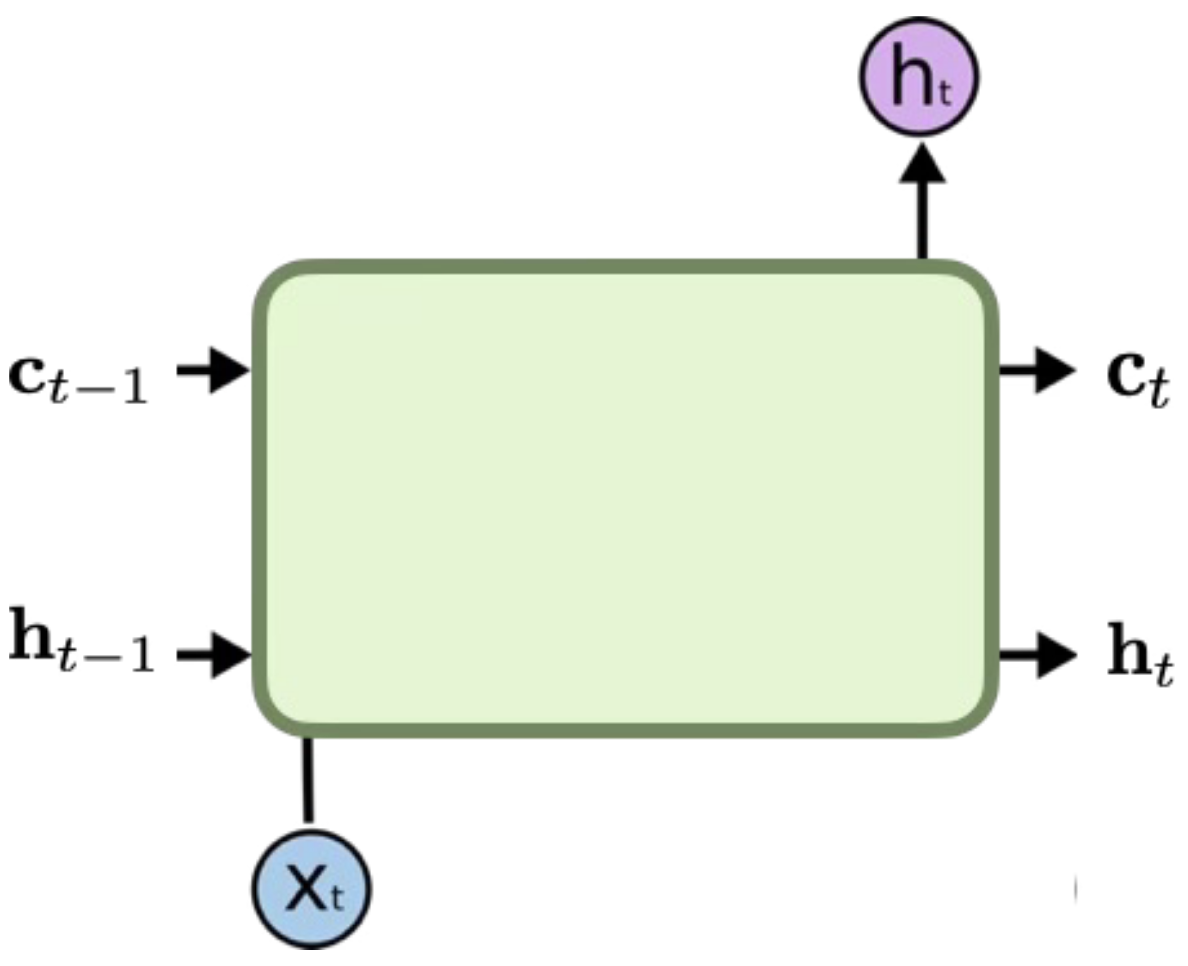

Recurrent Architectures such as RNNs, LSTMs and GRUs process sequences step-by-step using a hidden state .

Vanishing Gradients: Long sequences involve multiplying weights many times (). If , gradients vanish; if , they explode. LSTMs (Long-Short-Term-Memory) and GRUs (Gated Recurrent Unit) use “gates” to mitigate this and preserve long-term dependencies. LSTMs face several technical challenges, particularly when dealing with long sequences

Sequential Bottleneck: Because these architectures process data token-by-token, they are slower and more computationally expensive compared to parallel architectures like Transformers.

Memory Loss: On very long sequences, it remains difficult to maintain “long-term dependencies,” meaning the model may lose critical information from the start of the sequence by the time it reaches the end.

Fixed-Vector Bottleneck: In sequence-to-sequence tasks, forcing an entire input into a single fixed-length hidden state creates a bottleneck that limits performance on complex data.

RNN: Recurrent Neural Network¶

where is the hidden state at time , is the input at time , and is the hidden state of the previous layer at time or the initial hidden state at time 0.

Concept: Designed for processing sequential data (time series, text, audio) where the order matters and input length varies.

Mechanism: Unlike feed-forward networks, RNNs have loops. They maintain a hidden state () which acts as a short-term memory. At each time step , the network takes the current input and the previous hidden state to calculate the output and the new hidden state.

Key Issue (Vanishing Gradients): During backpropagation through time (BPTT), gradients are multiplied repeatedly by the weight matrix (). For long sequences, if weights are small, gradients vanish to zero (network stops learning); if large, they explode. This makes standard RNNs bad at learning long-term dependencies.

LSTM: Long Short-Term Memory¶

where is the hidden state at time , is the cell state at time , is the input at time , is the hidden state of the layer at time or the initial hidden state at time 0, and , , , are the input, forget, cell, and output gates, respectively. is the sigmoid function, and is the Hadamard product (element-wise multiplication).

Solution: Designed specifically to fix the vanishing gradient problem and capture long-term dependencies.

Architecture: Introduces a Cell State () alongside the Hidden State. The Cell State acts as a “highway” for information to flow unchanged if needed.

Gates: Uses sigmoid activation “gates” to control information flow:

Forget Gate: Decides what to throw away from the cell state.

Input Gate: Decides what new information to store in the cell state.

Output Gate: Decides what to output based on the cell state and input.

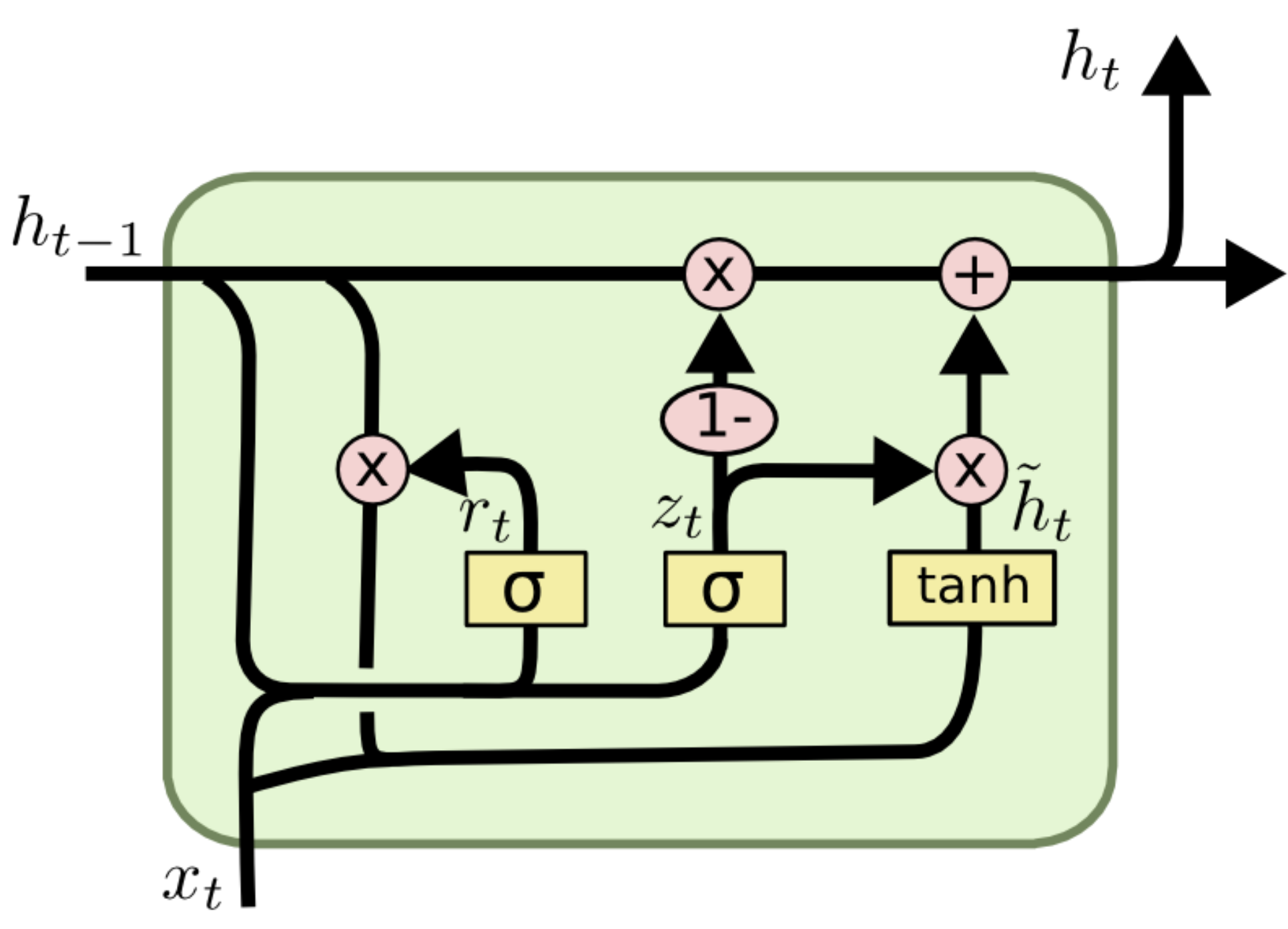

GRU: Gated Recurrent Unit¶

where is the hidden state at time , is the input at time , is the hidden state of the layer at time or the initial hidden state at time 0, and , , are the reset, update, and new gates, respectively. is the sigmoid function, and is the Hadamard product.

Concept: A simplified, more efficient variation of the LSTM. Architecture: Merges the Cell State and Hidden State into a single state. Combines the Forget and Input gates into a single Update Gate. Adds a Reset Gate to decide how much past information to forget.

Comparison: GRUs have fewer parameters than LSTMs, making them faster to train and often performing just as well on smaller datasets, though LSTMs may be more powerful for very complex tasks.

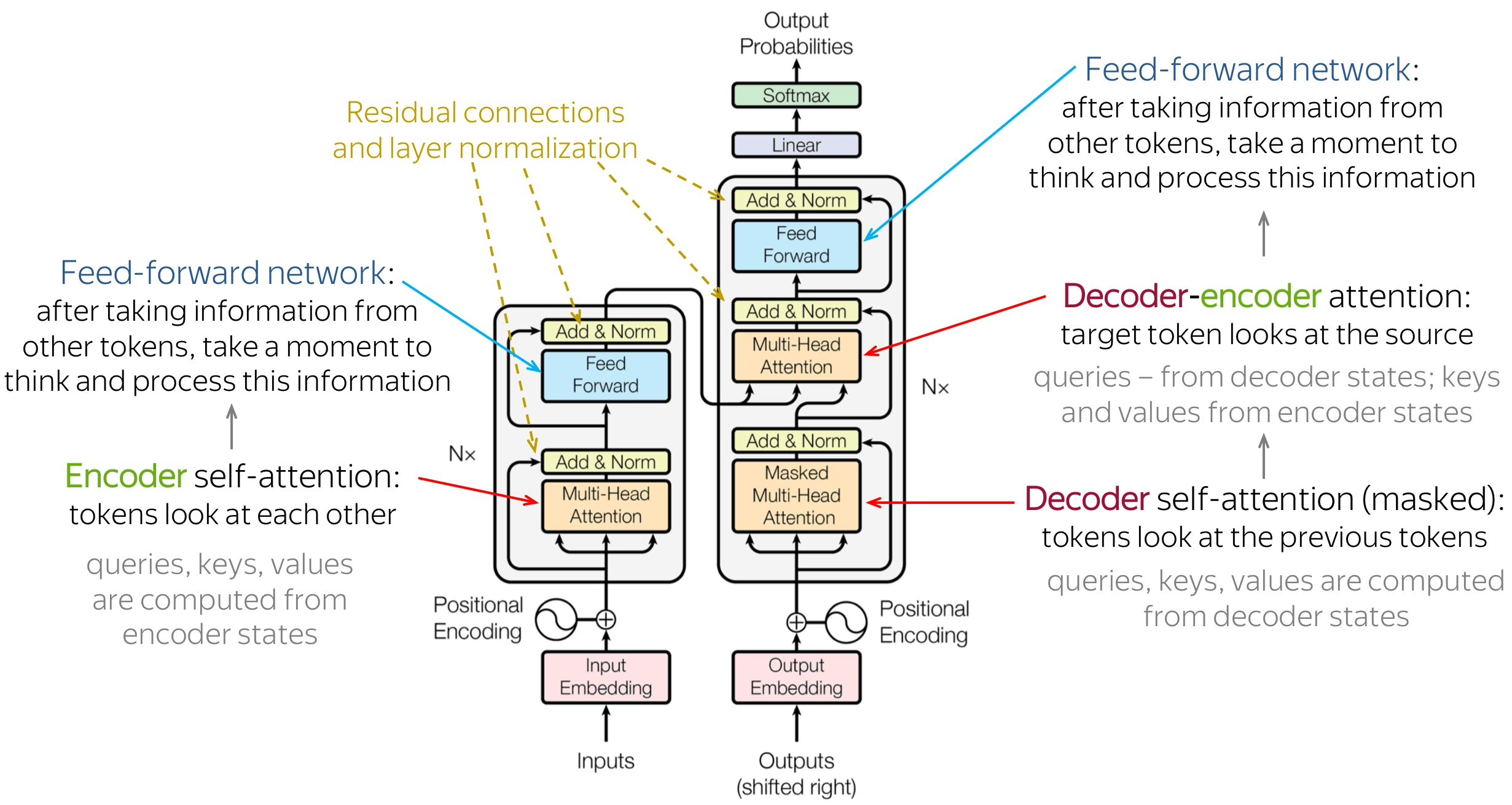

Transformers¶

The Attention Mechanism¶

Attention allows a model to “look back” at all positions of an input sequence simultaneously, solving the bottleneck of single-vector encodings.

The Trinity: (what I am looking for), (what I have), and (the information content)

Attention Score: The scaled dot-product between and (), the factor keeps variance at 1, ensuring stable gradients regardless of the input dimension :

Attention:

Transformer Architecture and its Goals¶

Minimize computational complexity per layer

Minimize path length between pair of words to facilitate learning of long-range dependencies

Maximise the amount of computation that can be parallelized

Self-Attention: , , and all stem from the same input sequence via different learnable linear transforms.

Multi-Head Attention: Uses multiple sets of to focus on different aspects of the sequence in parallel.

Positional Encoding: Since self-attention is permutation-invariant (order doesn’t matter), unique sine/cosine vectors are added to input embeddings to inject sequence order.

Decoder Training: In order that the decoder cannot cheat (in parallel training) and look at future tokens, we have to mask them out

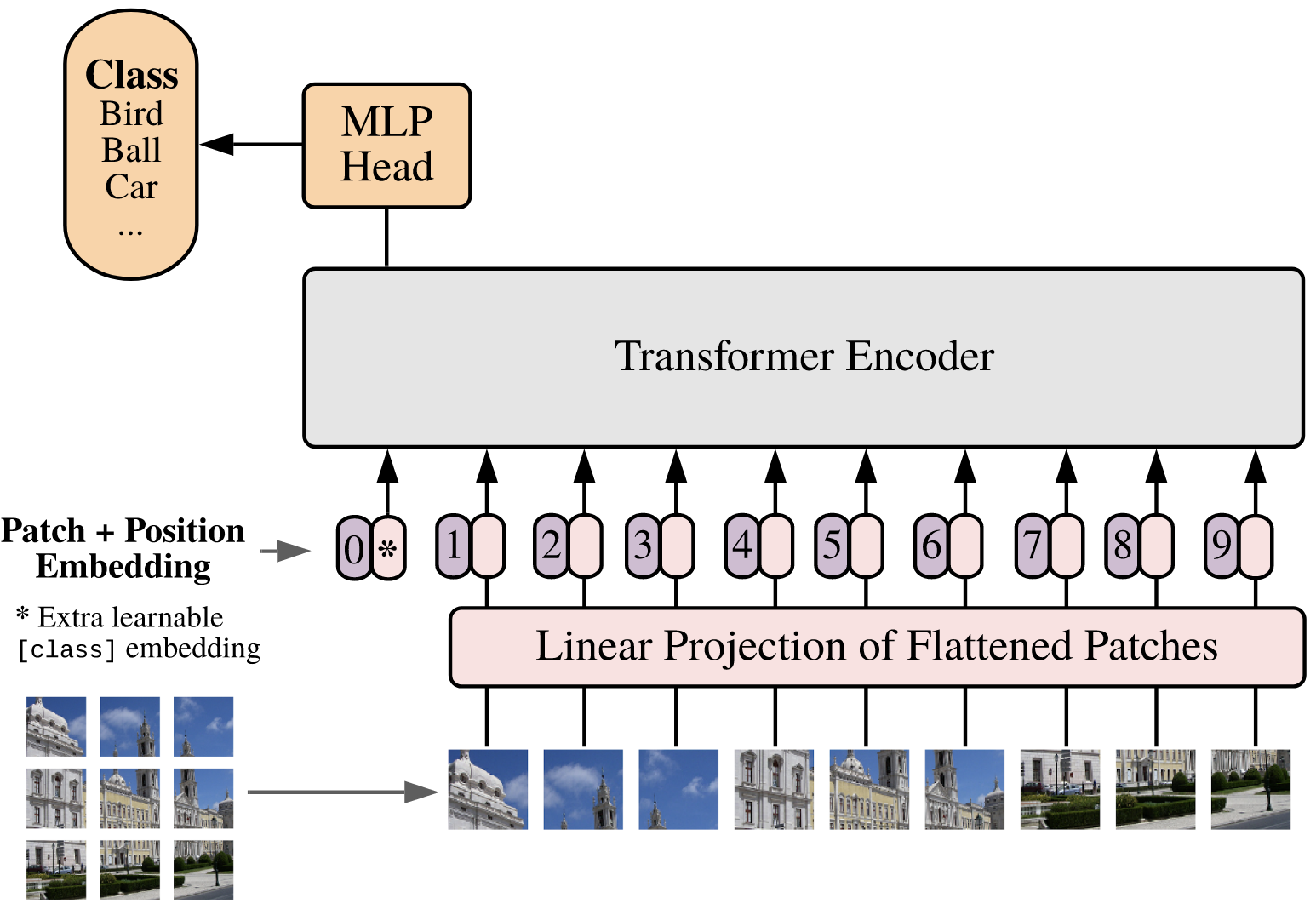

Vision Transformer (ViT): Images are split into patches (e.g., ), which are flattened and treated as tokens in a sequence for the transformer encoder.

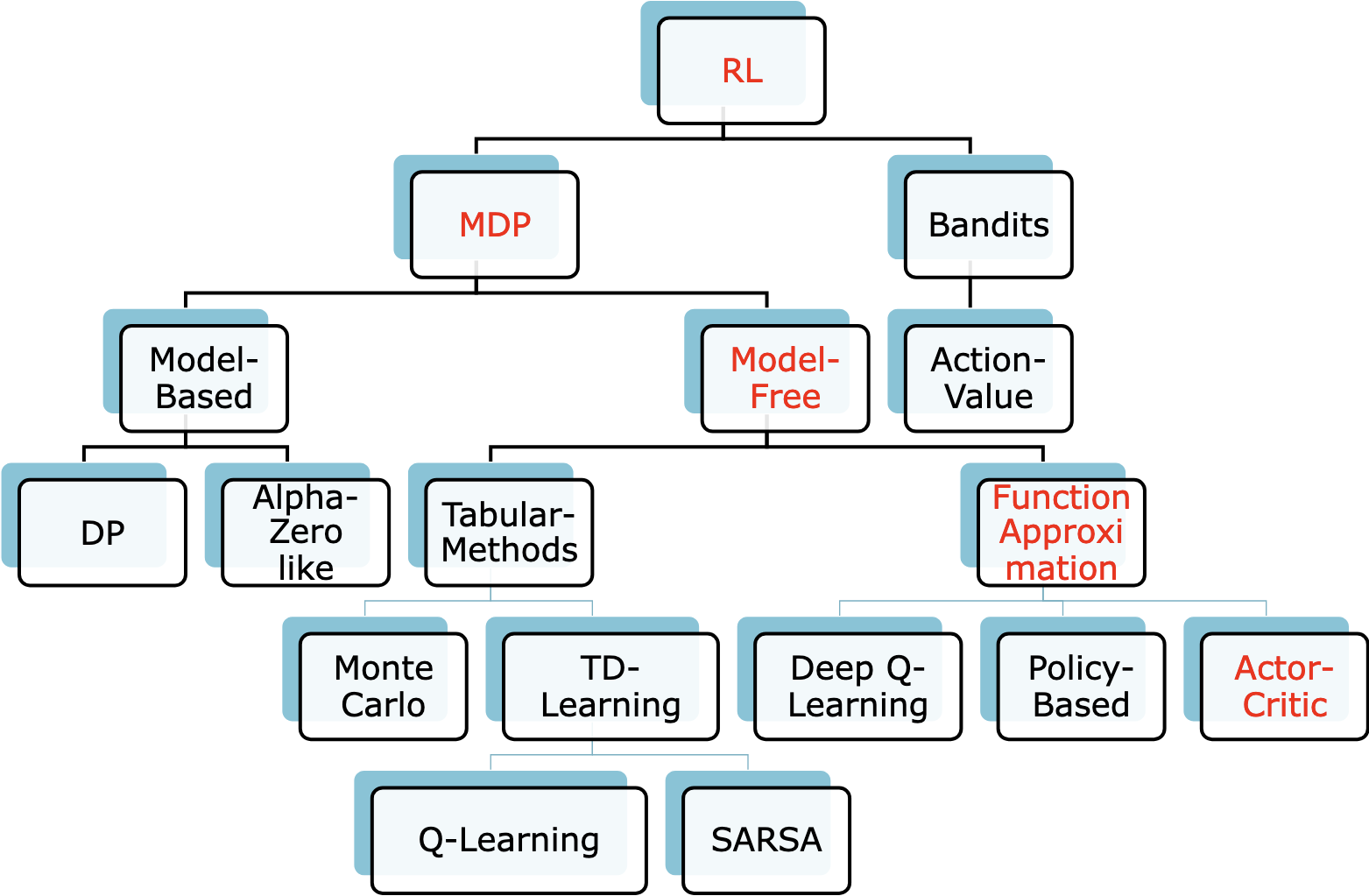

Reinforcement Learning (RL)¶

Reinforcement Learning Notation¶

action at time

state at time , typically due, stochastically, to and

reward at time , typically due, stochastically, to and

policy (decision-making rule)

action taken in state under deterministic policy

probability of taking action in state under stochastic policy

return following time

value of state under policy (expected return)

value of state under the optimal policy

value of taking action in state under policy

value of taking action in state under the optimal policy

Reinforcement learning methods specify how the agent’s policy is changed as a result of its experience.

Markov Decision Processes (MDP)¶

Goal: Maximize the Return (), the cumulative (often discounted) reward:

RL Key Algorithms¶

GNN: Graph Neural Networks¶

Deep learning architectures designed to process data represented as graphs (nodes and edges), such as molecules, social networks, or road maps. Unlike standard CNNs which operate on fixed grids, GNNs must handle irregular structures and varying neighborhood sizes.

Key Property: GNNs must be Permutation Invariant. The output must remain the same regardless of the order in which nodes are indexed in the input matrices.

Approaches:

Spectral Methods: Define convolutions in the frequency domain using the Graph Laplacian (e.g., GCN)

Spatial / Message Passing: Nodes aggregate information (“messages”) from their direct neighbors to update their own features (e.g., GraphSAGE).

Adjacency Matrix¶

The Adjacency Matrix () is a square matrix (where is the number of nodes) that mathematically represents the graph’s connectivity. Calculation Steps:

Initialize a matrix of zeros with dimensions .

For every connection (edge) between Node and Node , set the value at row , column () to 1.

If the graph is undirected, ensure symmetry: if , then .

Self-Loops: For many GNNs (like GCN), we add self-loops so a node considers its own features during updates. This means setting the diagonal elements to 1 ().

Example: Given a graph with 3 nodes where Node 1 is connected to Node 2, and Node 2 is connected to Node 3 (Note: With self-loops added, the diagonal would become ones):

GNN for Graph Classification¶

Graph classification predicts a label for the entire graph (e.g., “Is this molecule toxic?”) rather than for individual nodes. Architecture:

Input: Adjacency Matrix and Node Features .

GNN Layers (Message Passing): Several layers of graph convolutions update the embeddings for every node based on their neighbors. This captures local structure.

Readout (Global Pooling): A global aggregation step is required to compress all node embeddings into a single Graph Embedding. Common methods include Global Mean Pooling (average of all nodes) or Global Max Pooling.

MLP Classifier: The resulting single graph vector is passed through standard Dense/Linear layers.

Output: A Softmax layer produces the final class probability.

Explainable AI Nomenclature¶

Global vs. Local: Global explanations describe a model’s behavior across an entire dataset, while local explanations justify a specific prediction for a single instance.

Intrinsic vs. Post-hoc: Intrinsic models, also called glassbox or white-box models, are transparent by design (e.g., decision trees), whereas post-hoc methods explain “black-box” models after they have been trained.

Model-Agnostic vs. Model-Specific: Model-agnostic techniques can be applied to any architecture because they only use inputs and outputs, while model-specific methods rely on internal components like convolutional feature maps.

Surrogate Models: These are simple, interpretable models trained to approximate a complex model’s behavior within a localized parameter space.

Attributions and Saliency Maps: These terms refer to visualizations, often heatmaps, that highlight which parts of an input most influenced a specific model decision.

Counterfactuals: These provide “what-if” scenarios by identifying the smallest change needed in an input to flip the model’s output.

XAI Challenges¶

The primary challenges of XAI stem from the fundamental tension between model complexity and transparency: as models become more accurate, they generally become more opaque.

The Missingness Problem: It is difficult to define “nothingness” for a neural network without biasing the output. For example, using a black baseline (zeros) may be highly meaningful in certain data types, like sketches.

The Correlation Problem: Many methods assume features are independent, which can lead to non-physical explanations that do not respect the data’s true distribution.

Saturation and Vanishing Gradients: In well-trained models, the output can be so certain that small changes to individual pixels result in near-zero gradients, making sensitivity-based explanations noisy.

Computational Expense: Techniques like occlusion require thousands of forward passes, while calculating exact Shapley values is mathematically intractable due to the possible feature combinations.

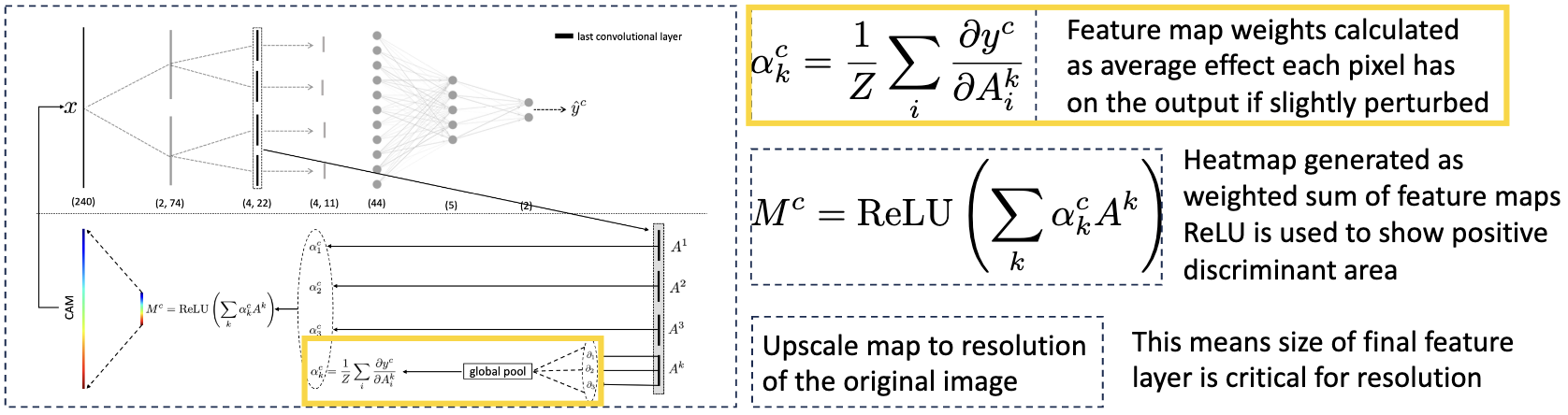

Resolution vs. Semantics: Model-specific methods like CAM and Grad-CAM face a trade-off where deeper layers provide high-level semantic meaning but suffer from low spatial resolution because the feature maps have shrunk.

Sensitivity to Hyperparameters: Explanations can vary drastically based on user-selected values, such as the kernel width in LIME or the chosen baseline in Integrated Gradients.

Glassbox Models¶

Glassbox or “white box” models are models that are intrinsically interpretable, not requiring additional techniques to understand their decisions. Common examples include linear models, where weights directly represent feature importance, and decision trees. Although these models often sacrifice accuracy for transparency, they serve as critical components in more advanced XAI methods like LIME and CAM.

XAI Plot Based Methods¶

Individual Conditional Expectation (ICE or ICPs) is a local explanation method that visualizes how a model’s prediction changes for a specific instance as one feature is varied,. While Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) show an overall average effect across a dataset, ICE plots a separate curve for each instance to reveal variations that might be hidden by aggregation,.

The procedure involves selecting a feature and sweeping its unique values for a single row while keeping all other feature values constant,. This allows researchers to identify heterogeneous effects, such as subsets of data that react differently to feature changes compared to the global average.

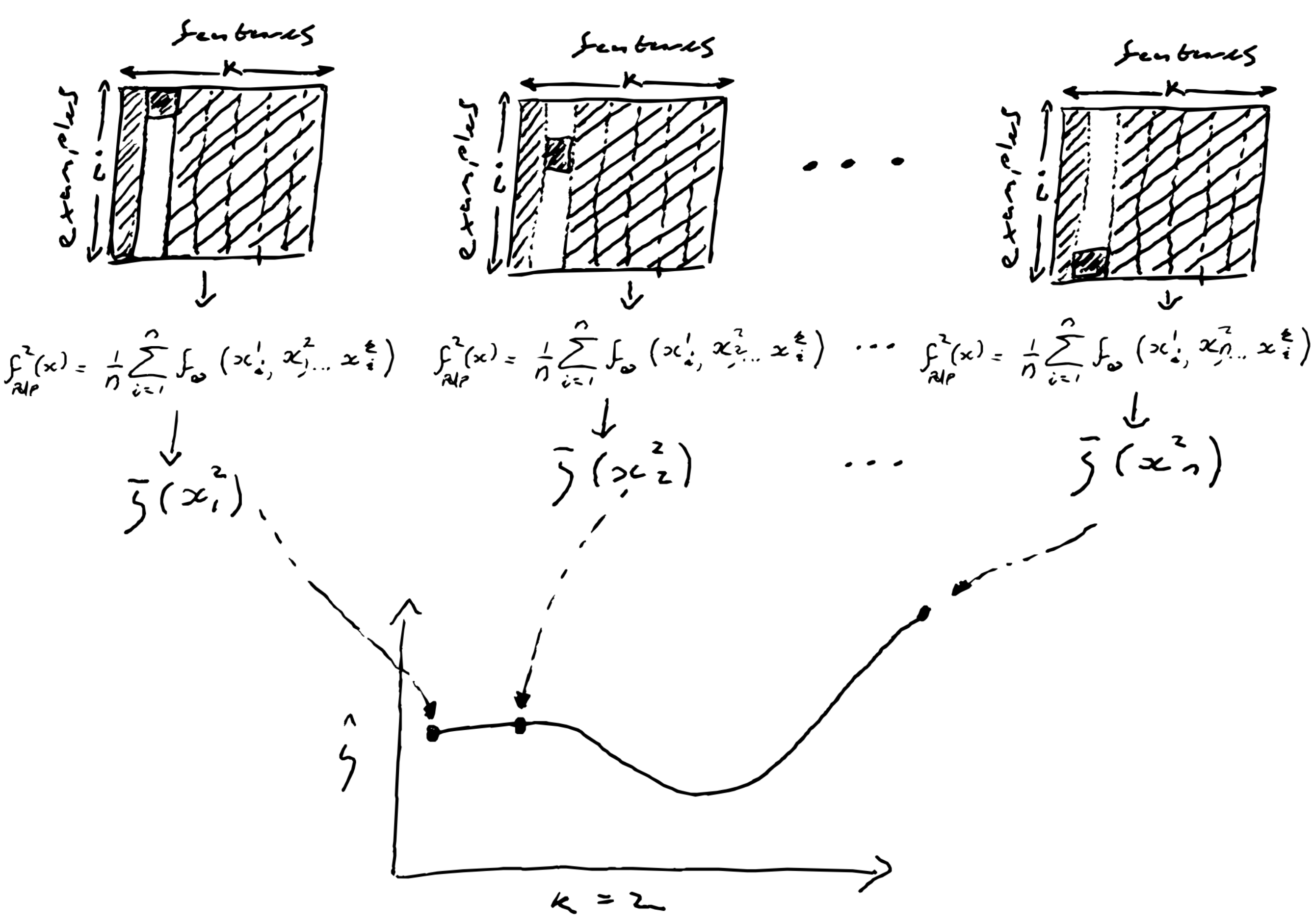

PDP: Partial Dependency Plot

First order approximation of feature dependence Assumes features are uncorrelated.

Select feature index to analyze ()

Find unique values for this feature

Order values of this feature in ascending order

Set feature for all instances and calculate the average

Repeated this for to i_n tracing out a curve

Vectorize by replacing entire column with single feature value

Problems: Examples might not be physical because features are most likely not independent. Also taking the marginal contribution over the entire dataset is likely to hide interesting cases.

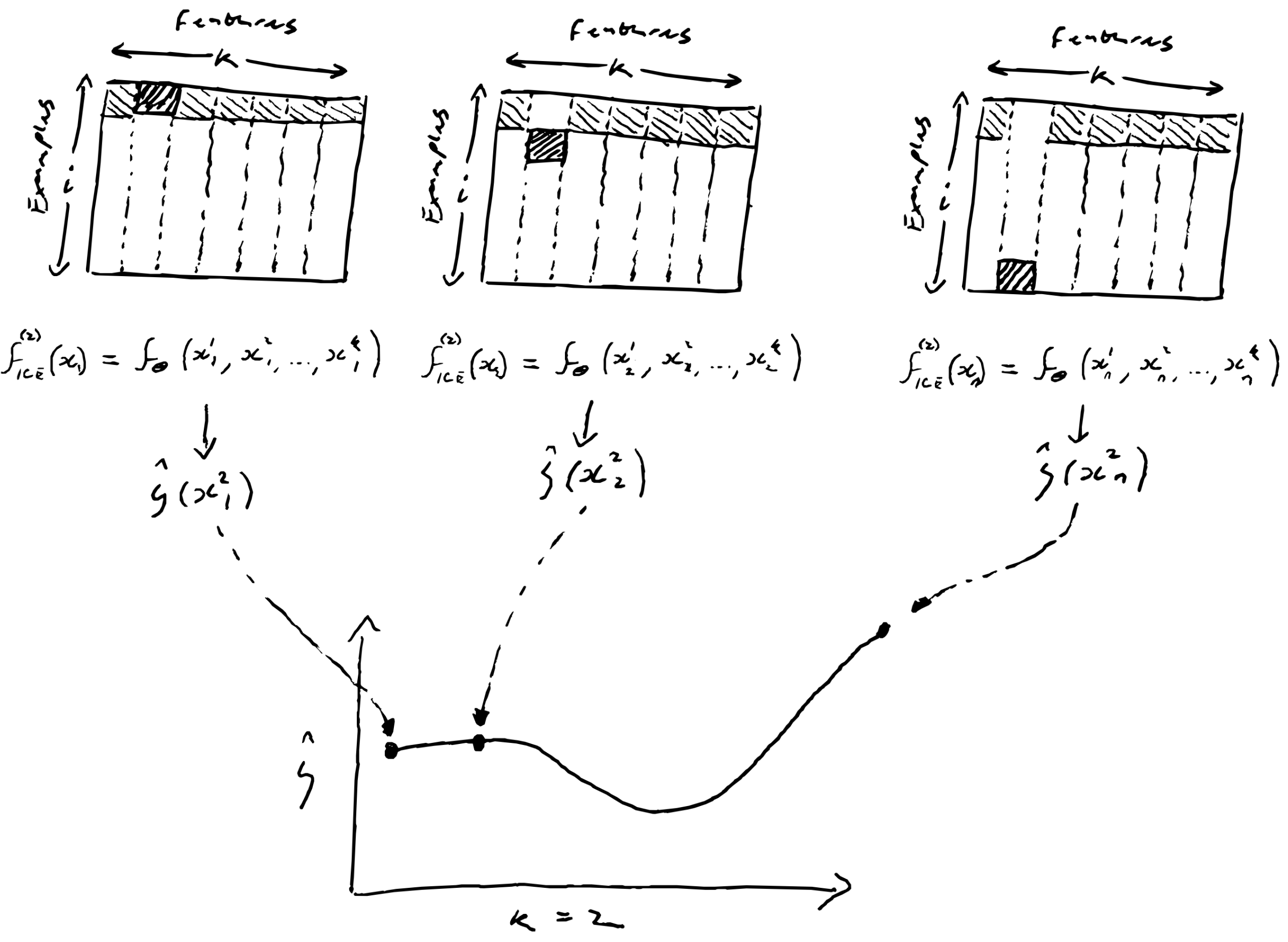

ICE: Individual Conditional Expectation Plot

Second order approximation of feature dependence.

Select feature index to analyze ()

Find unique values for this feature

Order values of this feature in ascending order

Take single instance and calculate BB-model output varying feature i over all its values to trace out a curve

Repeated for sub subset

Vectorize by duplicating for entire matrix insert column of unique values

Saliency Mapping¶

Saliency mapping (also known as heatmap or attribution mapping) identifies which parts of an input were most influential in a model’s specific prediction.

Occlusion and Adaptive Occlusion¶

Occlusion is a simple, model-agnostic method that identifies critical regions by “blacking out” portions of an input and measuring the change in the model’s output (Adaptive Occlusion attempts to minimize the occluded area while maintaining the same prediction output w/o occlusion). It produces a saliency map where regions that cause the largest prediction swings are highlighted as important. Its main drawbacks include high computational costs and extreme sensitivity to hyperparameters like kernel size and the chosen baseline value (e.g., black vs. noise).

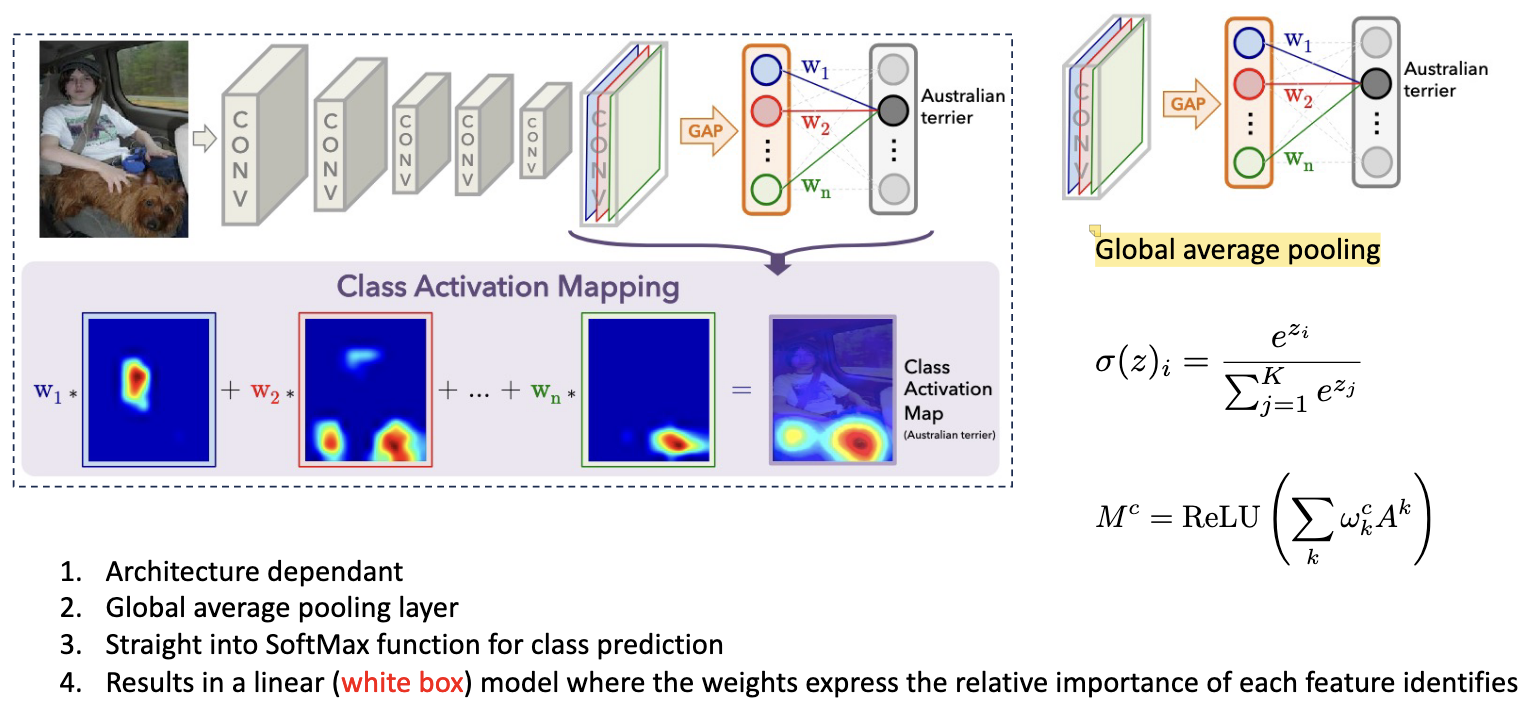

GAP: Global Average Pooling¶

Global Average Pooling (GAP) is a dimensionality reduction technique that computes the average value across all spatial dimensions of a feature map, reducing a 3D tensor to a 1D vector. It replaces fully connected layers at the end of convolutional neural networks.

Mathematical Definition: For a feature map with shape where is the number of channels, is height, and is width:

where is the output for channel , and is the value at position in channel .

Output shape: — a single scalar value per channel.

CAM: Class Activation Mapping¶

CAM is a model-specific: It requires a specific architecture (Global Average Pooling (GAP) followed by a linear layer). The convolutional feature maps are processed through Global Average Pooling (GAP) to create a linear model just before the final prediction. By multiplying these feature maps by their corresponding class weights and summing them (often using a ReLU), the model generates a heat map of the discriminant regions. While semantic quality improves in deeper layers, the resolution of these explanations tends to decrease as the maps get smaller.

Grad-CAM¶

Is more flexible than standard CAM because it uses gradients to weigh the importance of feature maps rather than requiring a specific architecture. Importance is assessed by “wiggling” individual feature maps and measuring the sensitivity of the output.

Frees up architecture constraints; Don’t have to compromise accuracy as final conv layer can go into any function, not just a SoftMax; Final feature map resolution dictates the graduality of the explanation; Tension between high level semantics and explanatory resolution; Cannot compare the intensity of final heatmaps between different instances; Still requires CNN.

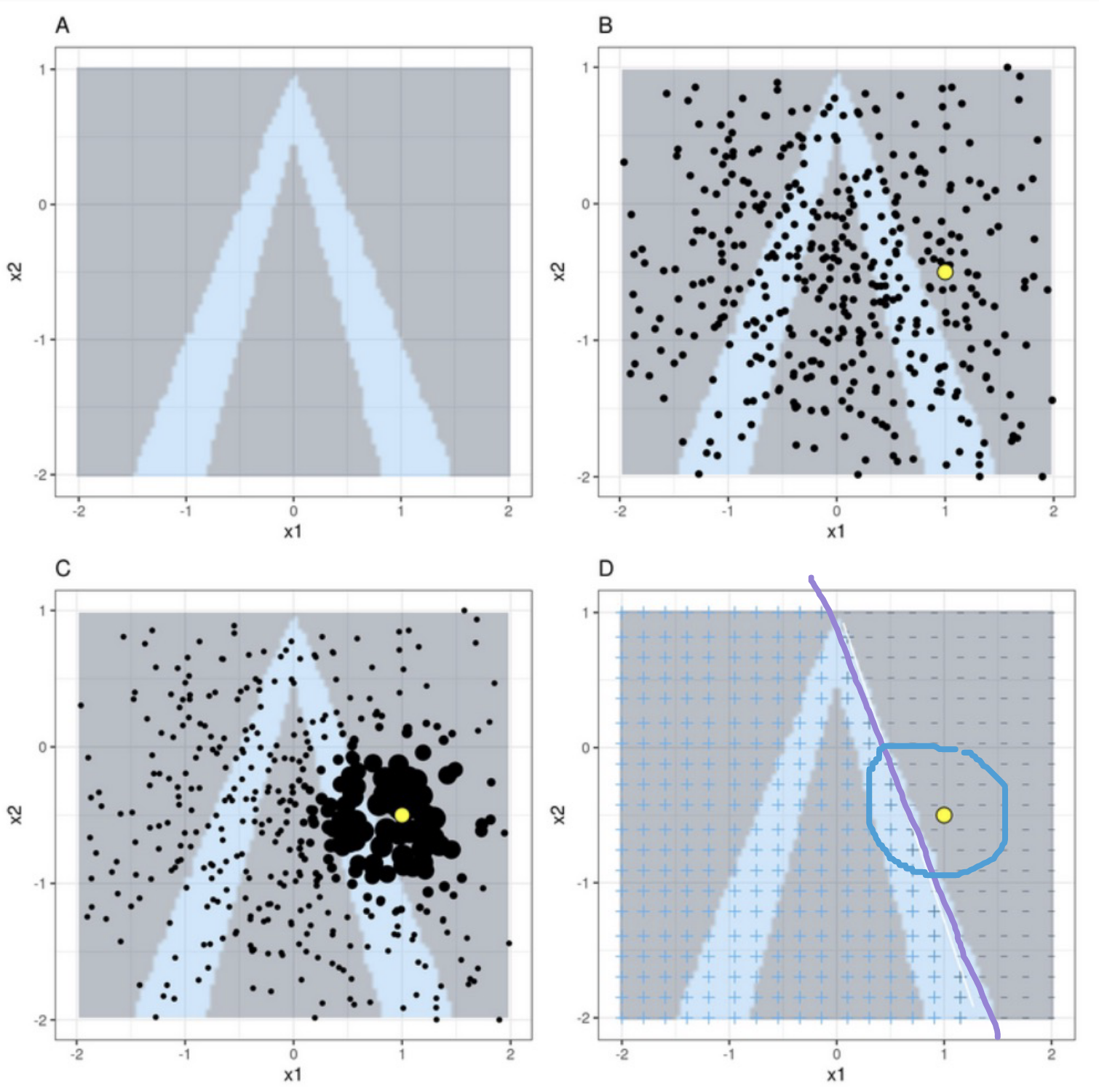

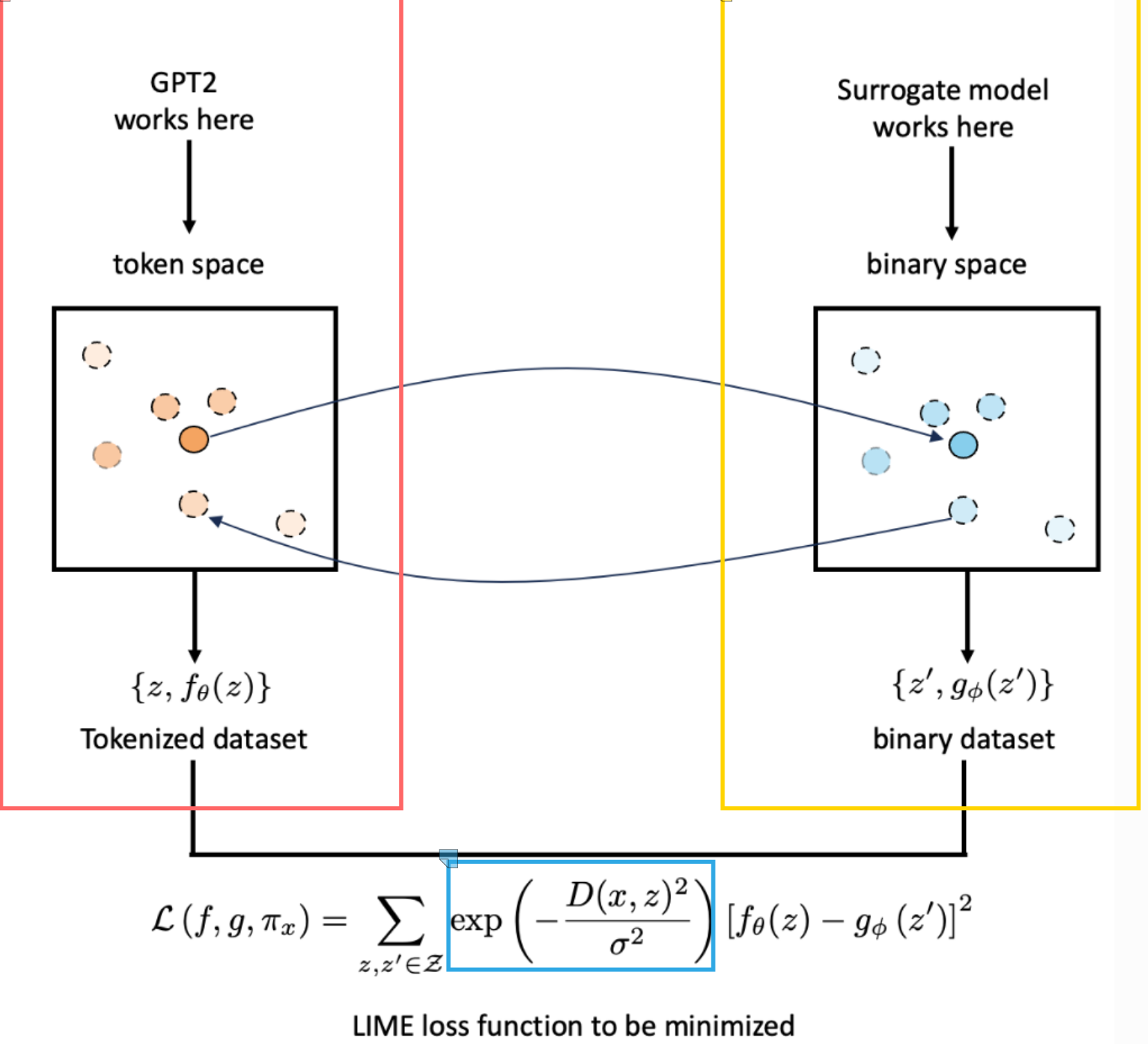

LIME: Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations¶

LIME is a model-agnostic method that provides “local” explanations for individual instances, working across tabular, text, and image data. It operates by randomly sampling data around a specific prediction and weighting those samples using a proximity measure - typically an exponential kernel - so that points closer to the original input are more important. A simple, interpretable surrogate model (such as a linear model) is then trained to mimic the black-box model’s behavior in that local neighborhood.

Basic Idea of LIME

Upper-left: Data with two features, x1 and x2. Classifier f labels class 1 blue and class 0 grey. Steps of LIME

Upper-right: We want to explain the yellow data point. Generate new samples (black dots).

Lower-left: Weigh the dots such that dots closer to the yellow point are more important.

Lower-right: Train a surrogate white box model g to label the new data points such that it behaves like our black box model (locally)

Left: Blackbox-Model, Right: Surrogate Model, Bottom: Enforces locality for predictions: If the distance is large, it should be less relevant if the prediction is different.

We want to explain the black box model f. Particularly it decision for the central orange point in the original unprimed data space. This point a sentence, row, or an image.

Transport the data point into a binary representation shown here as the dark blue central point in the primed data space.

Randomly sample data from the binary representation to generate a z’ dataset (other blue points).

Map the new sampled dataset back to the original image space such that we have an unprimed dataset z.

Train a white box model g on the primed dataset such that it has high fidelity, i.e., behaves the same as the black box model f when labelling the new dataset. Loss function can be seen at the bottom of the plot.

Use a proximity measure that places more weight on points similar to the original data point we want to explain (exponential kernel).

Local vs. Global Explanations¶

Local: Explains a specific instance (e.g., “Why was this loan denied?”).

Global: Summarizes feature importance across the entire dataset.

SHAP: Shapley Values¶

Based on game theory: how to fairly distribute the “payout” (prediction) among “players” (features).

Axiom of Completeness: The sum of all feature attributions must equal the model’s prediction minus the baseline.

Integrated Gradients: A path-integral method that integrates gradients along a line from a baseline (e.g., black image) to the target image to solve the saturation problem (where gradients go to zero in trained models).

Generative AI¶

Explicit vs. Implicit Density¶

Explicit: Models the probability directly (e.g., PixelRNN, VAE).

Implicit: Learns to sample from the distribution without explicitly calculating (e.g., GANs).

VAE: Variational Auto-Encoder¶

The VAE is a generative model that extends the AE structure to estimate the probability density of the data. Instead of mapping an input to a fixed point in the latent space, it maps it to a probability distribution. Optimizes the Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO). The Encoder approximates the posterior , and the KL divergence forces it close to a Gaussian prior.

Latent Space: The encoder outputs parameters for a distribution (Mean and Variance ) rather than a single vector. The system then samples from this distribution to feed the decoder.

Smoothness: The latent space is continuous, allowing for valid interpolation between points (e.g., morphing one image into another), unlike standard AEs.

Trade-off: VAEs are easy to train and fast to sample from, but often produce blurrier images compared to GANs,.

Loss Function (ELBO): The VAE optimizes the Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO), which consists of two competing terms:

Reconstruction Loss: Ensures the output resembles the input (Likelihood).

KL Divergence: A regularization term that forces the learned latent distribution to approximate a standard Gaussian prior (typically ).

Equation Insight: If the encoder models a Gaussian distribution, the KL term has a simple analytic expression involving and :

Inputs: The encoder network directly outputs the mean () and variance () for each latent dimension .

Result: This formula penalizes the network if:

diverges from 0 (the term).

diverges from 1 (the terms).

This insight refers to a computational shortcut that makes training Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) efficient.

Reparameterization Trick:

The Problem: In a standard VAE, the encoder outputs the parameters of a distribution (mean and variance ). The network must then sample a latent vector from this distribution to feed the decoder. This sampling operation is stochastic (random). Standard backpropagation cannot compute gradients through a random node, meaning the encoder’s weights cannot be updated to minimize the error.

The Solution: The reparameterization trick solves this by expressing the random variable as a deterministic function of the model parameters and an independent source of noise. Instead of sampling directly from , the model:

Samples a noise vector from a fixed standard normal distribution:

Calculates using the deterministic formula:

The randomness is now contained in , which is treated as a constant input during backpropagation. The latent vector is now a differentiable function of and , allowing gradients to flow from the decoder back into the encoder.

GAN: Generative Adversarial Network¶

The MinMax Game: A Generator creates fake images from noise, and a Discriminator tries to distinguish them from real data.

Minmax Loss:

WGAN: Uses the Earth Mover (Wasserstein) distance, to provide a stable gradient even if the generator and data distributions do not overlap.

CycleGAN: Learns style transfer between two domains without paired data (e.g., horses to zebras) using a Cycle Consistency Loss () to allow style transfer without paired training data.

SSL: Self-Supervised Learning¶

Pretext Tasks¶

The model solves “fake” tasks to learn a backbone representation.

Examples: Predicting image rotation, solving jigsaw puzzles, or colorization.

Success is measured by performance on downstream tasks (e.g., classification) using only a small amount of labeled data.

SimCLR: Contrastive Learning¶

Method: Create two augmented versions of the same image (positive pair) and maximize their similarity while minimizing similarity with all other images in the batch (negative pairs).

Order of Operations: Data Augmentation Encoder Projection Head Contrastive Loss.

Projection Head: A small MLP that “absorbs” the contrastive loss, allowing the encoder to maintain general features.

BYOL: Bootstrap Your Own Latent¶

Learns representations without negative examples.

Uses two asymmetric networks (Online and Target). The Target weights are an Exponential Moving Average (EMA) of the Online weights, preventing the model from collapsing to a trivial constant output and negative pairs.